The End Of The World, Part II: W. Olaf Stapledon

From the desk of Thomas F. Bertonneau on Fri, 2011-10-14 18:14

Given that the End of the World is an old eschatological myth that modernity has appropriated and secularized it is unsurprising that visions of Armageddon and the Last Judgment migrated, in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, to literature and indeed called forth from literature a new genre, the “scientific romance” or science fiction story. In that new genre the Late-Antique demonology alienated itself, populating the planets and stars with materialistically conceived counterparts of the devilish scourge that one encounters in Fifteenth-Century canvasses by Hieronymus Bosch and Mathias Grünwald.

In The War of the Worlds (1897), H. G. Wells (1866 – 1946) brought the story of alien invasion to its paradigm of articulation, from which every subsequent item in the subgenre stems, including such recent cinematic extravaganzas as Skyline (2010) and Battle: L.A. (2011). Wells himself returned to the alien-invasion motif with extraordinary subtlety and humor in Star Begotten (1937), but otherwise eschewed his own trope. For Wells, external doom seemed less plausible and less interesting than the many types of immanent catastrophe, which mankind, in its fits of historical repetition, has made for itself and will undoubtedly make for itself again. Part I of the present article has explored The End of the World in a number of Wells’ novels – The War in the Air (1906), The World Set Free (1913), and The Food of the Gods (1904). These novels reveal, beneath a deceptive surface whose assumptions appear to be those of a standard Twentieth-Century materialism, surprising insights about human nature and civilization that exist in considerable tension with a materialistic worldview.

Civilization takes hold, Wells argues, in what in The World Set Free he calls “vision,” “the subjugation of the self,” “the sense of unread symbols in the world,” or finding oneself “in the great being of the universe.” In his teens Wells had discovered such vision in Plato’s Republic, “a very releasing book for my mind” full of “tremendous significance” and a source of “encouragement… to give my wishes a systematic form.” So Wells writes of Plato in Experiment in Autobiography (1934). Of Marcus Karenin, the founder of universal education in the “World Republic” described in The World Set Free, Wells stipulates, “He saw religion without hallucinations, without superstitious reverence” and “he gave it clearer expression, rephrased it to the lights and perspectives of the new dawn.” As The World’s narrator editorializes, “Christianity was the first expression of world religion, the first repudiation of tribalism and war and disputation” and in that way anticipated the “World Republic.” Vision founds a world. The attenuation and extinction of vision spells death for a world. Wells’ Mind at the End of its Tether (1945) records the extinction of the modern West’s noetic coherence.

No successor of Wells understood this fundamental truth of civilized order better than Liverpool-born William Olaf Stapledon (1886 – 1950), Wells’ prophetic heir-apparent who is today – regrettably – even less read than his illustrious precursor. Narrower than Wells’ oeuvre, Stapledon’s oeuvre is more concentrated, more overtly vatic and mystic, closer in its bardic ecstasy to the dizzying sublimity of The Timaeus or The Divine Comedy. The claritas, the audacity, the scale, these in Stapledon humble the reader.

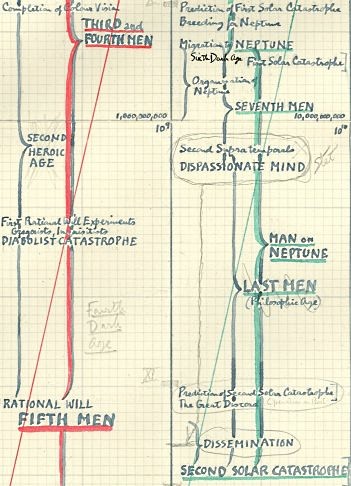

I. Not “Utopia” and “bliss,” but rather “huge fluctuations of joy and woe” constitute the subject matter of Stapledon’s Last and First Men (1930), a novel, supposing it to be a novel, so unprecedented in its ambit as to make even Wells’ Shape of Things to Come (1933) look cautious and limited in comparison. Last and First Men undoubtedly influenced The Shape, which borrows Stapledon’s framing device: Wells’ book presents itself as having been dictated telepathically across time by an economic and social historian of the year 2060, for whom a diplomat of the present hour has stood amanuensis. Stapledon’s Preface, addressing the readership, declares in the first person that “this book has two authors”; it describes how “a being whom you would call a future man has seized the docile but scarcely adequate brain of your contemporary, and is trying to direct its processes for an alien purpose.” Indeed, “We of the Last Men earnestly desire to communicate with you, who are members of the First Human Species.” The “Last Men,” the “Eighteenth Men,” call to their primitive ancestors from no less than two billion years hence, prompted by an “unexpected crisis,” a veritable “discovery of… doom,” whose deepening shadow blights the sublimity of their achievement. Despair colors the appeal, not least because “your acquaintance with time is very imperfect” and “your understanding of it is defeated.” [Stapledon’s italics all.]

2.jpg)

This spokesman-narrator, whose mood might bear the label of tragic objectivity, introduces one of Stapledon’s salient themes: That to realize their humanity fully descendants must cherish their ancestors while the ancestors-to-be must care, and not merely abstractly, for their descendants unto the remotest. It is partly a demand of Caritas in the Christian sense, partly a demand of Eros in the Platonic sense, but it is wholly a case of past, present, and future interpenetrating vitally and calling into question the paltry image of time as a mechanical succession of moments. For Stapledon time, which can only mean human time, obeys a tragic muse, under whose tutelage the race in bouts of hubris and humiliation endures ordeals and prostrations, always of its own willful making, again and again. That from “petty cause [comes] mighty effect” is one law of Last and First Men; that “opinionated self-deceivers” invariably outnumber and overwhelm men of “dispassionate intelligence” is another. For Stapledon, whose plotline expresses itself in symphonic movements on a Wagnerian scale, the immense agony of humanity’s eighteen punctuated phases takes shape as the fugitive, often discordant counterpoint of two great motifs that announce themselves in the earliest flowering of the “First Men”: “Socrates, delighting in the truth for its own sake and not merely for practical ends, glorified unbiased thinking, honest of mind and speech. Jesus, delighting in the actual persons around him, and in that flavor of divinity which, for him, pervaded the world, stood for unselfish love of neighbors and of God.”

Novice readers of Last and First Men must have faith that its bewildering mass of incidental detail will resolve in an intelligible pattern. Testing Stapledon’s mettle as a near-term prognosticator will perhaps sustain the intrepid through those of the book’s early chapters that serve as extended prologue to the description of the global Americanized civilization, “The First World State,” in which the First Men find their stultified destiny. Stapledon grasped in 1930 that World War I had dealt a coarsening blow to the Western spirit. He foresaw that endless new conflicts would stem from the botched armistice. In Last and First Men, exponentially more violent wars devastate Europe. The destructive spasms leave a planet dominated by two poles, America and China, both demoralized, not to say demented, by a century of holocausts. As for America: “The best… was too weak to withstand the worst,” while the worst, like “bright, but arrested, adolescents,” embodied “the intolerant optimism of youth.” (A striking phrase!) Of American culture as it aggressively assimilates the world, the narrator remarks that nothing so summed it up as “the merging of Behaviourism and Fundamentalism, a belated and degenerate mode of Christianity,” in a benighted and parodic creed.

In the narrator’s and presumably Stapledon’s judgment, “Behaviorism itself… had been originally a kind of inverted Puritan faith.” Whereas “the older Puritans trampled down all fleshly impulses” and whereas “these newer Puritans trampled no less self-righteously upon the spiritual cravings”; nevertheless this “most materialistic of Christian sects” and this “most doctrinaire of scientific sects” soon devised “a formula” whereby “to express their unity,” no less than “the denial of all those finer capacities which had emerged to be the spirit of man.” In the birth of the World State, then, a crass scientism in the trappings of the phoniest mysticism establishes itself as the global cult of “the Divine Gordelpus” (Stapledon’s nominalization of the old Cockney expletive, “Gawd ‘elp us”) overseen by the “Sacred Order of Scientists” (“S.O.S.”), which obliterates all other confessions. In universal, compulsory adherence to this cult, and under a calendar of perpetual obligation, the planetary citizenry celebrates that quintessentially American mania, “the fanatical worship of movement.” Divinity being energy and energy being movement, the doctrine calls people to worship Gordelpus through constant kinesis in physical sport and religious ritual. Worshippers also dedicate themselves formulaically to “progress,” another type of movement, but it remains a verbalism without an actual correlation. Although the First World State lasts four thousand years, it is technically, culturally, and in every other way static.

The Americanized planet boasts a material achievement that, as the narrator puts it, “would have amazed all its predecessors,” in which “the whole energy of man was concentrated on maintaining at a constant pitch the furious routine.” Such frenzy betokens to the Last Men only a “thorough confusion of material development with civilization,” even as it reminds present-day readers uncomfortably their own agitated, gadget-clogged environment. It had come to pass that “all the continents were by now minutely artificialized” and “all were urbanized.” Perfections of metallurgy and polymer-chemistry permit “the erection of buildings in the form of slender pylons which, rising often to a height of three miles… and founded a quarter of a mile beneath the ground, might yet occupy a ground plan of less than half a mile across.” Such vaulting structures “were scattered over every continent in varying density.” An immense air-traffic swarms everywhere. The cruciform structure of the airplane having suggested a half-forgotten sacred symbol, aeronautics becomes another ritual expression of divine motion in extravagant “Days of Sacred Flight.” These displays acquire a distinctly sacrificial character. Much else in the prevailing culture also speaks of a sacrificial resurgence.

The madness of it can hardly portend anything save a suicidal crack-up, which, though postponed, knocks abruptly when it befalls. “Clouded minds” have supposed the sources of energy inexhaustible. In fact, having tapped the usable fossil reservoirs elsewhere, the World State has latterly and desperately been extracting energy through the burning of Antarctic coal in situ. This resource too now approaches depletion. In hurried response, “all luxury trades were abolished, and even vital services were reduced to a minimum,” while “workers thrown out of employment were turned over to agricultural labor.” The mandatory catechism having taught everyone since childhood “to shun curiosity as the breath of Satan,” never to inquire and never really to think, humanity can no longer muster the intellectual acuity to cope with the crisis. Mobs turn on the priestly officers of the “S.O.S.” The hapless elites, desperate to save themselves, unleash poison gas and weaponized viruses against the ubiquitous rioters. Soon it fell out that “only in the most fertile areas of the world could the diseased remnant of the population now scrape a living from the soil.” Now indeed, “with easy strides the jungle came back into its own” and a “Dark Age” of “utter desolation” settled over the world.

II. Literate people recognize the name H. G. Wells even when they have never actually read him. Even among literate people, however, the name William Olaf Stapledon (he rarely used the “William”) means little. Who was Olaf Stapledon? While the secondary bibliography remains sparse, two significant items grace it. One, a literary study by Leslie Fiedler (1983), made Stapledon academically respectable. The other, a splendid biography by Robert Crossley (1994), offered the first full account of the rather shy and modest man behind the fearless prophetic authorship. Born to upper middle class affluence, the native of Liverpool and namesake of a Viking convert attended the cautiously unconventional Abbotsholme School, founded by William Blake enthusiast Cecil Reddie. On leaving Abbotsholme Stapledon matriculated at Balliol College, Oxford, earning degrees in history, a baccalaureate in 1909 and a magisterium in 1913. Crossley remarks that Stapledon’s only surviving Oxford essay praises Jeanne d’Arc, that auditor of voices, for her visionary heroism in France’s English wars. Like Wells, Stapledon attempted what Crossley characterizes as the “tragicomedy of… schoolmastering.” In 1911, the better to make himself marriageable, Stapledon prevailed on a paternal connection to obtain employment in the Ocean Steamship Company. “For two years,” Crossley writes, “he… sampled the shipping business in two of the most extraordinary ports in the world,” Liverpool and Port Said, only to discover that “the bourgeois securities of a management post” held no allure for him.

Returning to Liverpool, Stapledon took lodgings in a working class neighborhood, read, wrote, and lectured under the sponsorship of the Workers' Educational Association. In 1915, not exactly a conscientious objector and not exactly a patriot, he joined the Friends Ambulance Corps and went to war as a driver. Stapledon’s experiences in combat color the early chapters of Last and First Men and become the explicit subject matter in its sequel, Last Men in London (1932). As Crossley tells, Stapledon’s Section Sanitaire came under fire at Reims in 1917: “The attack was bloodier than anything he had yet witnessed; one ambulance was bombed into scrap-iron, and two drivers were seriously injured.” In November 1918 just before the armistice Stapledon earned the Croix de Guerre for bravery under fire. Stapledon’s spectacular fables of civilizational collapse and destruction have, given their author’s first-hand experience, an immediate validity missing in their counterpart passages in Wells although this is not to disparage Wells, who was too old for frontline service, in combat or otherwise.

Stapledon’s saga has not quite finished with the First Men, whose phase as the First World State acquires at length a modest sequel. One hundred thousand years pass between the fall of the First World State and the rise of a new and tentative civilized order in Patagonia. The narrator speculates on the causes of these dilatory fallow millennia. Not only had “four thousand years of routine… deprived human nature of all its suppleness,” but also “a subtle psychological change,” a “senescence of the species,” had sapped the racial spirit. “For during some thousands of years man had been living at too high a pressure in a biologically unnatural environment.” It helps not that the catastrophe’s barbarized survivors live in hovels beneath the ruined towers, which an emergent myth identifies as aeries of the departed gods. The Patagonians represent the belated flowering of an Andean proletariat that had played only a marginal role in the constitution of the previous civilization. As the narrator writes, however, the Patagonian phase of the First Men unfolds “in a minor key.” Short-lived, the Patagonians “began to grow old before their adolescence was completed.” Moreover, “their sexual impulse was relatively weak.” A fatalistic melancholia pervades their existence.

The Patagonians nevertheless reconstitute civic order and industry. Absent coal and oil they first base their physical plant on wind-power and hydrodynamics; later they discover the secret of atomic disintegration, which the First World State had never mastered. The central episode of the Patagonians, however, is the career of “the Divine Boy,” in whose pronouncements the Socratic and Christic motifs find new expression. The Divine Boy also reincarnates Friedrich Nietzsche’s Zarathustra – or the Übermensch whom Zarathustra forecasts – in Stapledon’s adaptation of the Existential anthropology that also crops up in Wells (for example, in The Food of the Gods). The Divine Boy seems to be a biological sport whose physical constitution defies the rule of senescence-in-youth; he is also robust, both intellectually and sexually. His career as religious reformer recapitulates elements of the Socratic and Christic ordeals: “He preached the religious duty of remaining young in spirit. No one… need grow old… if he would but keep his soul from falling asleep.” And, “Delight of soul in soul… was the great rejuvenator.”

The Divine Boy, also called “The Son of Man,” once interrupted the solemn rites in the main tabernacle where “all [were] prostrated before the hideous image of the Creator.” In words that Stapledon might have taken from Thus Spake Zarathustra or The Twilight of the Idols, the joyous prophet “burst into a hearty peal of laughter, slapped the image resoundingly, and cried, ‘Ugly, I salute you!’” The profanation shocks every sentiment of Patagonian religious somberness, but “such was the young iconoclast’s god-like radiance… that when he turned upon the crowd, they fell silent, and listened to his scolding.” The sermon that follows echoes “O Great Noontide” from Zarathustra, completing which the prophet “picked up a great candlestick and shattered the image.” The society cannot tolerate the trespass of so many taboos, so “not long afterwards [the Divine Boy] was tried for sacrilege and executed.” In suppressing him, naturally, the Patagonians deny their better angels, dooming themselves to the consequences of their deeply seated neuroses.

A debilitating blow falls when the Patagonians dig up archeological evidence of the First World State. The truth flashes on the people “that all the ground which they had painfully won from the wild had been conquered long ago, and lost; that on the material side their glory was nothing beside the glory of the past.” The knowledge overwhelms them “that the past had been not only brilliant but crazy and that in the long run the crazy element had completely triumphed.” The epochal knowledge destabilizes Patagonian society, splitting it into a self-denominating “progressive” part that assimilates ancient knowledge, including technical knowledge, and a conservative part that clings to tradition. The progressive part subdues the conservative part in a series of wars, unifies the planet, and pursues the problem of atomic energy, about which the First World State knew, but which it never mastered. Patagonian science unlocks the secret and applies it industrially. The end comes when, during a labor dispute, rebellious mineworkers, seizing a power unit, fumble its operation.

“The first explosion was enough to blow up the mountain range above the mine,” from which center the mischief spreads globally in “an incandescent hurricane… like a brood of fiery serpents.” The narrator notes, ominously but in passing, how, “Martians, already watching the earth as a cat a bird beyond its spring, noted that the brilliance of the neighbour planet was enhanced.” The sole survivors of the catastrophe are the fourteen members of an expedition sent to explore the Arctic Circle. In material wretchedness, this nucleus of the human species separates after an argument into two groups, one of which, after ten million years, will give rise to the “Second Men.”

III. The destruction of the Patagonians comes about through the moral affliction that Nietzsche dubbed ressentiment. As the narrator puts it, “a petty dispute had occurred in the mines.” (Emphasis added) It is a case once again of the law, “from petty cause… mighty effect.” Worker-resentment comes, tellingly, from the intrusion of étatist arrogance into private life: “The management refused to allow the miners to teach their trade to their sons; for vocational education, it was said, should be carried on professionally.” For all parties being seems to lie elsewhere. For the Patagonians as a whole, being seems to lie with the precursor-civilization, whose image bestrides like a colossus their racial imagination. The miners feel abused and thwarted by scientific management, while the supervisory class, seeing the miners’ family-tradition as out of step with rationally regulated life, resents the autonomy of spirit that it guesses to lie behind pride and stubbornness. Atomic energy has become the symbol par excellence of elite status, which the miners therefore covet and the supervisors withhold. Stapledon has incidentally stumbled on what might be a truth in myth and legend – that catastrophes have now and again reduced humanity to a precious few. DNA analyses of the existing global population point, for example, to “genetic bottlenecks” in the racial history. In the worldwide Toba extinction seventy thousand years ago the living sample of Homo sapiens dropped to as few as fifteen thousand.

Last and First Men qualifies as an encyclopedia of hypothetical disasters, each generation of the human species from the First Men to the Eighteenth Men being foredoomed to suffer, much as the heroic generations in Greek tragedy are foredoomed to suffer. Stapledon’s book recapitulates every disaster in the Wellsian oeuvre and adds not a few that Wells never imagined. Crossley compares Last and First Men to Paradise Lost, as “a story of human paradise repeatedly lost and regained and ultimately lost for good, but with Miltonic theology edited out.” Fiedler writes, “In the universe as imagined by Olaf Stapledon, no triumph, material or spiritual, is forever.” Perhaps Stapledon, as Crossley argues, wrote Miltonic theology out of his saga; but he never wrote theology out of it, even as he cast false religiosity, zealotry, and bigotry as pernicious sources of social degeneration. Thus the civilization of the Second Men succumbs to an interminable jihad waged against the Earth by Martian fanatics. In The War of the Worlds, the Martians take sick and die from earthly bacteria; in Stapledon’s “War of the Worlds,” the Martians are bacteria, or rather viruses, and yet there is something familiarly human about them.

Martian civilization like its terrestrial counterpart has run a roller-coaster ride of crises, collapses, near-suicides, and agonized reorganizations. Certain events in Martian racial development afflict the planetary mentality more severely and generate greater perversity of conscience than anything in Stapledon’s speculative human parallelism until the decline of the Second Men. Martian consciousness arises only in the aggregate, the individual “sub-vital” units having no self-awareness unless joined magnetically and telepathically in organized “cloudlets,” through which the race thinks and constructs. The “cloudlet” communal-minds “were [thus] hobbled by their sameness,” lacking in “the rich diversity of personal character,” and “almost wholly devoid of the passion of love.” In their ascent to planetary dominance the Martians have perpetrated “racial massacres” of all competing intelligences and a “joyous massacre” of their final competitor. They have devised a sophistical doctrine to the effect that “the extermination was a sacred duty.”

The Martians’ usual state being an organic aerosol, and their effective state being only a viscous “jelly,” they bestow on rigidity “peculiar sanctity.” The attitude develops into “fanatical admiration of all very rigid materials, but especially of hard crystals, and above all of diamonds.” In the Martian reconnaissance of earth, what the “cloudlet” perceives as sacrilegious mishandling of talismanic stones becomes the pretext of an implacable sectarian campaign: “They came… in a crusading spirit, to ‘liberate’ the terrestrial diamonds.” So bizarre is Martian behavior that humanity only gradually grasps that an aggressive deliberate power has come interfering, which nothing save organized lethal force can dissuade. On the Second Men, innately social and affectionate, the necessity of counter-violence, although inarguable, falls hard – all the more because the war recurs destructively for fifty thousand years. Men repeatedly rebuild from the wreckage, believing in the value of their Sisyphean struggle, until at last despite their philosophical resolve “to see their own racial tragedy as a thing of beauty… they had failed.” Nihilism saps the civilized spirit. The terrestrials in desperation unleash a microbe, which effectuates genocide of the Martians on both worlds, “but at the cost of annihilating also the human race.” Only a crippled handful survives.

Stapledon offers one of the keener, and one of the most entertaining, Twentieth-Century critiques of ideology. It is a cause for regret that Eric Voegelin, who was aware of science fiction as the expression of quirks and insights of the modern mind, never commented either on Wells or Stapledon, about whom he might have had fascinating things to say. Ordinary people who are not steeped in and whose consciences are therefore undistorted by ideological fanaticism almost never see Puritanical intolerance for what it is. Perhaps that is the ordinary man’s ideology. He projects his own preference for minding one’s business and thereby gives a great tactical advantage to his chauvinist enemies. Stapledon’s Martians conform to a completely submissive ethos; they shun independent thought even more than do the First Men in the cultic rottenness of the First World State. The group-mind regards the slightest heterodoxy as apostasy and mobilizes itself immediately to eradicate it. Like the stultified societies known to actual history, Stapledon’s Martian society has been historyless since its murderous self-consolidation, a “changeless efficient super-individual” bent on assimilating everything in the cosmos to itself. Nodding at Thomas Hobbes, Stapledon remarks, “The Martian super-individual was Leviathan endowed with consciousness.”

Stapledon’s term crystallization and his related pejorative usage of rigidity belong to the modern analysis of doctrinal implacability. Both words imply unalterable fixation of life in a mechanical pattern, the character of which is to resist the intrusion of any complicating element. In his non-fictional Waking World (1934), Stapledon identifies spiritual vitality, the capacity for honesty and self-transcendence, with vulnerability to “revelation.” The individual passes from childhood to adulthood and from adulthood to philosophy in those moments, “so to speak, when large tracts of its experience, or the whole of its experience, suddenly or gradually acquire a new significance, when it ‘com-prehends’ things in a new pattern, opens up new vistas of intellectual significance or new illuminations of feeling, and consequent new determinations of will.” Of course, “individuals… differ in respect of their degree of mental and spiritual aliveness.” The best society fosters and rewards intellectual vivaciousness and refuses to evaluate it equally with psychic torpor or resentment. The best society keeps the essential virtues of Socrates and Jesus, objectivity and love, in generative balance while it actively stigmatizes bigoted reductionisms, such as Behaviorism and Fundamentalism.

IV. Readers interested in further details of Last and First Men between the Second Men and the Eighteenth Men might seek them either in Stapledon’s text or in the relevant chapter of Fiedler’s Man Divided, which entails much rich summary. Fiedler, a one-time Trotskyite and lifelong Leftist, oddly enough chides Stapledon for his supposed “anti-Americanism,” but he otherwise does justice to his subject. As for Stapledon himself, in constant fertile invention he remains unsurpassed among speculative writers, and in his tragic vision of the human condition he has only gained power with the passing decades since his death. In their remote era two billion years hence, the Eighteenth Men face humanity’s terminal crisis, while in their demise Stapledon illustrates the old Greek proverb that whom the gods would destroy they first drive mad. Madness and vision maintain obvious connections. Stultified social consciousness sees vision as madness; real vision, under persecution, can devolve into frustrated dementia. In imitating a charismatic prophet, the followers will literalize his metaphors and reduce his clairvoyance to so many dumb fossils of insight. Where Plato respected the idea of Socrates’ “demon,” crass skeptics made that entity a mere pretext for lampoons and dismissals. In the rhythm of Stapledon’s chronicle, readers will perhaps sense something respondent to Oswald Spengler’s feeling for the seasonal finitude of the Great Cultures. Stapledon might well have agreed with Spengler that when a society has reached its “New Comedy” phase of sarcastic skepticism – when it succumbs to the delusion that ridicule is thinking and mockery is knowledge – it has bled out the last of its life energy.

The overarching narrative device of Last and First Men is that a man of the distant future, whose society faces the ultimate crisis, communicates the saga of humanity to an individual of the present day (“W.O.S.”), who, unsure whether the experience counts as life or dream, offers it as fiction. Last and First Men qualifies as a latter-day Platonic “true myth,” much as Stapledon’s posthumous Opening of the Eyes (1954) qualifies as a latter-day Augustinian “confession.” The Eighteenth Men inhabit a much-transformed Neptune during the sun’s swollen, “Red Giant” phase; the Last Men, brought about through bio-engineering by the previous “Seventeenth Men” so as to consummate human potentiality, synthesize in their being the highest traits of all the previous humanities.

The theme of cognitive access beyond egocentric personal awareness to exalted collective awareness occurs in Wells, but almost always within the limits of purely sociological knowledge. The identical theme surfaces often in Last and First Men, but in Stapledon the sociological restriction less encumbers it than it does in Wells. The Eighteenth Men, a telepathic race, live in complicated multi-party sexual arrangements (something much more than the nucleated family), whose members on regular occasions merge into a group-mind; and these group-minds on less frequent, quasi-ritual occasions merge as a single, temporary “racial self” or “mind of the race.” In this state the participant-individual “sees with all eyes… perceives at once and as a continuously variegated sphere, the whole surface of the planet.” He possesses for a moment “philosophical insight into the true nature of space and time, mind and its objects, cosmical striving and cosmical perfection.” The experience exceeds language, as mystic glimpses do. Of “the austere form of the cosmos” the seer afterwards “can scarcely be said to remember more… than [its] extreme subtlety and extreme beauty.”

Neptunian society, an “anarchy” rooted in “a very intricate system of customs,” corresponds to the mystic vision, taking life from it, as also do Neptunian science and religion, which have entered into the balance of creative unity. In their ethics, the Eighteenth Men “try to regard the whole cosmic adventure as a symphony now in progress, which may or may not some day achieve its just conclusion.” Theirs is the closest approximation of social and cultural perfection achieved by any of the successive humanities, which at its height gives prospect of as yet unachieved but truly godlike new developments. At this most propitious hour, however, in “a near star,” an unprecedented “paroxysm of brilliance” occurs, the radiations of which have soon “infected with… disorder” the primary of humanity’s solar system. The diseased radiations of the sun in turn exert degenerative effects on the Neptunians, who foresee rapid decline into mental illness, de-coherence of their society, and unavoidable extinction. In an act of “supreme filial piety,” the Last Men invest all remaining mental élan in psychic exploration of the past, hoping to ameliorate bygone suffering by influencing history through surrogates. “We seek to afford intuitions of truth and value, which, though easy to us from our point of vantage, would be impossible to the unaided past.” Possibly Socrates and Jesus and the Divine Boy are such surrogates. Insanity nevertheless creeps on the Last Men. They know that death looms.

Last and First Men thus concludes in an event that implies an absolute limit, a cosmic horizon, restricting technical progress and social perfection, as though the universe militated itself to thwart hubris. Only in a Beyond – distantly sensed but without detailed resolution by the Neptunians and into which humanity shall never enter – might entities superhuman and incomprehensible carry the utopian scheme further than the Last Men have carried it. Stapledon’s title, Last and First Men, resonates with a line from the Sermon on the Mount, where Jesus promises that in the eschatological rectification, “the last shall be the first.” Just not in this world. In his programmatic books, Stapledon advocates a type of socialism, but this socialism differs from the Marxist variety in rejecting the dialectic of materialism as a sufficient basis either for physics, on the one hand, or for anthropology, on the other. The “truth and value” of which the Last Man speaks are not relative, but absolute; knowledge of them comes from the glimpse into “the austere form of the cosmos,” where “form” has a Platonic connotation.

The idea of “filial piety,” or respect for what Stapledon elsewhere calls “the best tradition of the human race,” also departs from Marxist epistemology; it embraces, rather than rejects, the cultural inheritance, endowing it with the prestige of paternal wisdom despite, as Marxists would say, its irrational character. “I am by nature,” Stapledon writes in Saints and Revolutionaries (1939), “sympathetic toward scepticism”; and yet, he adds, “for that reason I feel bound to be critical of it.” This is because, “Scepticism is capable of becoming a fetish and of doing great harm.” Systematic skepticism that never puts itself under scrutiny contributes to “scientism,” which rejects any knowledge not derived from rigorous induction.

Of Stapledon’s other novels, Star Maker (1937) forms an indirect sequel to Last and First Men, being an account of intelligence in the entire cosmos unto the entropic heat-death of the universe. Odd John (1935), Darkness and Light (1942), Sirius (1944), and The Flames (1947) all maintain a relation to Last and First Men; A Man Divided (1950) is strongly autobiographical and retrospective. The Last Men In London likewise draws on autobiographical memory. Fiedler finds the non-fiction regrettable; he recommends his audience not to read it. I would say that Fiedler’s judgment is regrettable; it smacks of snobbishness. Waking World (1934) and Beyond the Isms (1942) are of more than passing interest. They rise to popular philosophy in the best sense, without special language or terms, and aimed at a lay audience that Stapledon knew well from the Workers’ Educational Association.

“I am not a Communist,” Stapledon repeatedly said in newspaper interviews and lectures during his participation in and his activities around the notorious “Scientific and Cultural Conference for World Peace” whose venue was the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, Manhattan, from 25 to 27 March 1949. The main public sponsor, the “National Council of the Arts, Sciences, and Professions,” fronted for the Communist Party USA; the actual sponsor, Stalin, hoped for a propaganda coup in the Megalopolis of North America. Stapledon, who had written so much about America, but who had never traveled there, naturally jumped at the chance. An independent thinker, he felt certain that audiences would understand his independence, not associating him with the strident isms that otherwise characterized the affair. Finally, the long-time prophet of doom saw in the appearance of nuclear weapons a mortal great token of humanity’s penchant for immolating itself on the cultic altar. He must speak. That the prophet of doom, who was also an evangelist of hope, miscalculated in some of these considerations – almost no one in America except a few science fiction fans had so much as the slightest notion of him – must not be held against him.

New York seems to have been a deeply scathing experience for Stapledon; he never quite recovered from his bruising. He died from a massive coronary thrombosis on 6 September 1950. His survivors, including the wife who outlived him, scattered his ashes in the Dee Estuary, which he loved.

(For Dirk Buyse, Richard Cocks, Steve Kogan, Michael Presley, and the students of “E-376”)

@Thomas

Submitted by antibureaucratic on Sun, 2011-10-16 11:02.

Looks like Stapledon was right then (about the Versailles Treaty leading to a renewal of war). Although one might argue that it would have happened anyway. Thanks for your reply (and the link)!

@antibureaucratic

Submitted by Thomas F. Bertonneau on Sat, 2011-10-15 14:08.

Crossley’s biography represents Stapledon as having contemplated seeking a commission through Oxford, which several of his Balliol College co-alumni did. He was not a pacifist and was not against Britain’s participation in the war, but he disliked the idea of ordering men to their deaths, the lot that might have befallen him had he gone as an officer to the front. He preferred non-combatant risk-taking, a role that the Friends Ambulance Corps offered. Stapledon’s Croix de Guerre demonstrates amply that he took risks, substantial ones. I linked Stapledon’s own account of why he joined the FAU in the article, but here it is again. Stapledon makes his reasoning at the time quite clear and his course of action quite plausible.

The contrast between Stapledon and Wells deserves an additional observation or two. Wells was older than Stapledon by twenty years, so of course there was no question of his joining up; but Wells, who was fervently anti-German, acted in effect and quite on his own initiative as a pro-war propagandist. Stapledon believed that Britain and France must defend themselves against Germany, but he had no animosity against Germans, whose cultural achievements he admired. Wells applauded the punitive character of the Versailles Treaty; Stapledon criticized it and predicted that it would lead to renewal of war.

Apocalyptic and post-Apocalyptic authors

Submitted by antibureaucratic on Sat, 2011-10-15 10:45.

It is hardly surprising that a lot of authors who went through WWI turned to this type of Apocalyptic theme in their writing.

Some notable mentionables include Henry Treece, Norman Cameron, W H Auden etc.

It was, after all, the war to end all wars, and when November 11 came most people assumed there would be no more all out world-encompassing wars.

Of course, the same was assumed on the conclusion of WWII particularly given the invention of Nuclear Weapons.

Regarding Stapledon's service in WWI - Wikipedia states that he served as a conscientious objector "with the Friends' Ambulance Unit in France and Belgium from July 1915 to January 1919." This may be because he was a pacifist, or it may simply be that 28 was generally regarded at the time as a bit old for frontline duty for an inexperienced soldier. Does the Author of this post have any thoughts on this?

Stapledon

Submitted by antibureaucratic on Sat, 2011-10-15 10:24.

Thanks for the introduction to this Stapledon character - I shall have to read some of his works - looks very interesting indeed!