The Shell of the Great Church

From the desk of Joshua Trevino on Wed, 2006-11-29 17:25

The Hagia Sophia is a tragedy in being.

At the center of old Constantinople stood the Church of the Holy Wisdom -- the Hagia Sophia. Where the great cathedrals of the West took decades or centuries to erect, the Hellenized Romans of the eastern Empire built the largest house of worship in Christendom in just five years. And they did so in the depths of the Dark Ages -- and it is still the largest free-standing domed church on the planet. The Hagia Sophia is a testimony to the genius and glory of what Dimitri Obolensky called the Byzantine Commonwealth. But it is more than a mere testament to material prosperity or strength of will: it is a monument to an enduring faith. By the time the Emperor Justinian commissioned the Hagia Sophia, Christianity had been in the ascendant over the paganism of antiquity for nearly two centuries. Multiple Church councils had gone by, and the Empire was shrinking dramatically. Still, if there was an effort to be made, this was it. Not on an imperial palace, nor on a monument, nor on a battlement -- which might have been the more sound investment for the Constantinopolitan -- but on a place of prayer.

When the Turk's hired Christian engineer sapped the Theodosian walls to claim the Queen City for Islam, the tale is that Mehmet the Conquerer spent days exploring the recesses of the Hagia Sophia. It was the great prize of the great city -- and when the Sultan emerged, he pronounced himself well pleased. He had the Great Church stripped of its nine hundred years of decoration -- glorious gilt and mosaics -- and caused minarets to be built at its corners. Hagia Sophia was now a mosque. Its Muslim occupants did not bother to rename it: instead, its Greek name became its Turkish one as well -- Ayasofya, a word meaning nothing in Turkish beyond the unintended invocation of the Holy Wisdom. Throughout the Ottoman period, the Christians of the east yearned for a Liturgy to be sounded again in the Hagia Sophia. At the end of that period, it seemed as if it might come to pass: one of the demands of the European powers, prior to the recognition of Ataturk's republic, was that the Hagia Sophia again be a church. Ataturk would not hear of it -- but he did make it a museum, and that was sufficient for the powers of Europe.

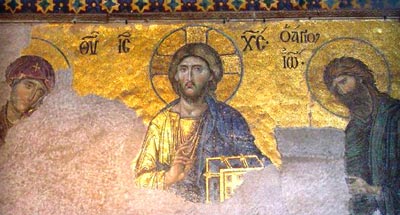

Thus the "Ayasofya Museum" came into being. The Muslims had ejected the Christian God from the Hagia Sophia, and the Kemalists ejected a God of any stripe. The functionaries of the new Turkish state stripped the walls of the whitewash of the Ottoman period, revealing some mosaics and some paintings long since forgotten. They are pitifully few. The older ones shine with the brilliance of late antiquity, and the newer ones -- if products of the late medieval period may be called new -- reflect the rough fortunes of late Byzantium. But there are a mere handful. Partly this is because of Ottoman destruction of imagery; and partly this is a reflection of the lackadaisical caretaking of the Turkish authorities. The Hagia Sophia is a tragedy in being; and the fate of its Christian art is especially poignant. Of especial note is the once-glorious mosaic of the Virgin, Christ, and John the Baptist on the upper level. When the Turkish Republic stripped the Ottoman whitewash in the 1920s, it was found preserved whole. Eighty years later, nearly two-thirds of it is gone, its tesserae ripped from the walls by looters and souvenir-seekers. A pathetic little photograph is now pasted to the wall beside its remains: this is what it used to look like, before it was victimized not by time, but by carelessness and apathy.

The Great Church is a dead shell. One enters it, and one is struck by its immensity and antiquity. But then, as one walks about it, one is struck by something else: its stasis. The house of God has no God in it, no worshippers of any kind, and no future to complement its past. The other great churches of Christendom are at the least well-preserved, and most even have active congregations. Aggressively secular Paris manages to find congregants -- and funds -- for Notre Dame. The Basilica of St Peter retains an active glory. St Mark's in Venice, nearest to the Hagia Sophia in decor and form, is yet alive with something more than tourists. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem is patrolled by prickly monks of various denominations. With the exception of St Peter's, I have been to all of these, and now, this morning, to the Hagia Sophia. I have seen the great spaces of Christianity. And among them, only the Hagia Sophia is dead. It is a metaphor and a warning -- of the Ecumenical Patriarchate under the Turks, and of Christianity under Islam.

There is another legend that precedes that of Mehmet the Conquerer's aesthetic stroll through the Great Church. When the Turks overran Constantinople, they hacked the last Emperor to death till only his boots remained, purple with the double-eagle insignia, and soaked in blood. Then they swarmed through the city to its signal prize. Inside, they found the last of the Romans worshipping at the last of 900 years of liturgies in the Hagia Sophia. They killed some and drove off the others. All this is true. The legend concerns the fate of the priests celebrating that final service: It seems the Turks rushed toward them, intent upon rendering them martyrs. The priests seized their paraphernalia and the remaining Eucharist -- and disappeared into the wall behind the iconostasis. When Christianity returns to the Hagia Sophia, they will reemerge from the very stuff of the Great Church and complete their worship.

It is mere legend. But miracles do happen. And the resurrection of the Hagia Sophia, by means of a single Liturgy said there, would be miracle enough.

A new photoset, of black and white shots of the old center of Istanbul at night, is now available here.

For those of you, who

Submitted by Mike Fessler on Thu, 2006-11-30 15:53.

For those of you, who understand German, here an excerpt of book by Stefan Zweig about the last days of Constantinople:

http://myblog.de/kewil/art/31005116/

Very nicely written

Submitted by JFP on Thu, 2006-11-30 15:37.

But I have a minor quibble. It wasn't the Dark Ages in the Byzantine empire when this was built. It was the Dark Ages in western Europe only.

No Turkish EU Entry Unless Hagia Sophia is Returned

Submitted by Mission Impossible on Thu, 2006-11-30 04:55.

Joshua's fine piece leads us all, I believe, to a clear and inescapable conclusion:

No Turkish entry into the European Union, unless and until the Hagia Sophia is returned, with full pomp & circumstance, to Christendom.

We must re-take full possession of the Hagia Sophia, dismantle the minarets, and do what we can to restore the interior back to its original condition.

The sounds of the liturgy must be heard again within its confines and witnessed on world-news television.

The city's name should also revert back to Constantinople.

Only when that is done can Turkey (subject to other, economic, criteria) be properly considered "a-kind-of" European country, and negotiations can begin.

If these preliminary conditions are not met, or flatly rejected, then we shall know the truth of Turkey's motives.

Are the homosexuals, feminists, and communist scum who presently run Brussels listening? Because if they aren't, they will soon be made to listen, as their backsides are kicked right out of the door.

A church as spiritually empty as its' future.

Submitted by siegetower on Thu, 2006-11-30 03:54.

Yes, great article. Historical yet contemporary. And quite tragic.

____

Defend Christendom. Defend Jewry. Oppose socialism in Europe.

Wow.

Submitted by Tito on Thu, 2006-11-30 01:52.

Great article!