Not with a Whimper - Part 2

From the desk of Howard Schwartz on Mon, 2012-08-13 20:51

In Part One of this essay, I discussed the role of police hesitancy in contributing to the spread of the British riots. The issue there was where aggression was turned; whether outward, in the form of physical destruction, or inward, in the form of guilt. That the rioters turned their aggression outward was essentially definitional. What was odd was that it was the police, who should have been in the business of suppressing the destruction through force, were unable to do so because their aggression had been turned inward. Britain was being burned down and they were the ones who were feeling guilt.

This is clearly a matter that beggars rational understanding, and so we will look to understand its irrationality.

A good place to begin is with the declaration by Sir Paul Condon, Commissioner of London's Metropolitan Police Service, on February 24, 1999, that his force was "institutionally racist."

He didn't have much choice, truth to tell. A public tribunal had made that charge, and the pressure on him to accept it was unbearable.

Now, in Condon's own mind, he had made the situation better than it could have been. He had to acknowledge "institutional racism", but he did arrange to have it defined by reference to "unwitting prejudice and ignorance." His idea was that this definition would save the individual police from the accusation that they were all racists.

But if he thought there was a difference, he was the only one. Specifically, the cops took it as a betrayal. They knew, as anyone could have known, that whatever nuances were intended, those who were inclined to charge racism would see individual police as representing the police force. So if it was officially called racist, they could be so called, and the contents of their minds were quite beside the point.

For our purposes, however, what is more important is that, in acknowledging institutional racism, he was conceding that the problem was part of the system. In effect, it established guilt as essentially a structural feature of the police organization; it was intrinsic, and could not be gotten beyond. From that point onward, any steps taken by the police to impose the social will on individuals of a non-white race, especially blacks, would be automatically suspect. It is easy enough to see how this could have led to a hesitation in imposing order on black rioters in the Summer of 2011, but in order to have a fuller sense of what was going on here, it is necessary to see how this came about, and for that, a bit of history is necessary.

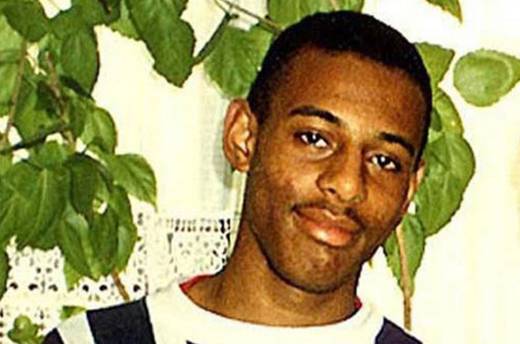

The best place to start is with the murder of a young black man named Stephen Lawrence on the night of April 22, 1993.

Lawrence, a person whose blamelessness in this incident has never been seriously questioned, and a friend, Duwayne Brooks, were waiting for a bus in a predominately white area of South London. He was set upon by a group of five or six young white thugs. One of the thugs shouted "What, what! Nigger!" and stabbed Lawrence, who shortly died of his wounds.

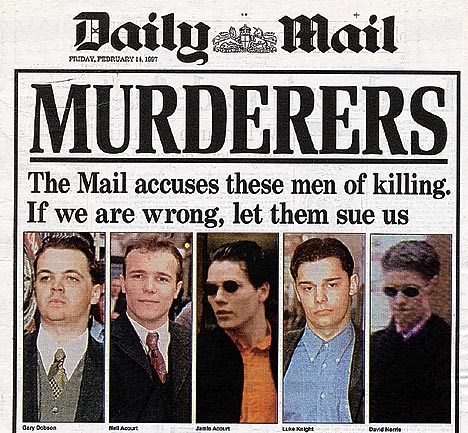

The police response to the attack, and the immediately subsequent investigation, were extensive, but not entirely competent. It soon focused, based on information from people in the neighborhood, on a group eponymously named the Acourt gang. We now know, on the basis of DNA analysis, that these were, indeed, the attackers. However, at that time, although several members of the gang were arrested, the evidence was ruled by the Crown Prosecution Service to be inadequate to sustain a conviction, and they had to be released.

By this time, however, the incident had become an international cause célèbre, and this dénouement was unacceptable. So the investigation continued and was reinvigorated. Still, the authorities could not acquire information which they believed would be sufficient evidence for a conviction.

The Lawrence family, however, could not accept this judgment and began a private prosecution of some of the gang members, which began on April 17, 1996. In that trial, which received full police cooperation, the gang members were acquitted, due to the inadequacy of the evidence.

From a legal standpoint, that should have been the end of the matter, given England's established principle of "double jeopardy." which prevented suspects from being tried again, once acquitted, even in a private prosecution.

But Mrs. Lawrence said that the acquittal had come because the trial was a sham.

Its purpose was to make a statement to the black community, which was that their lives were worth nothing. The British justice system would support any white person who wanted to kill any black person. As a black person, she said, her son had been stereotyped as a gang member and a criminal. "Our crime was living in a country where the justice system supports racist murderers against innocent people"

They brought the matter to the Police Complaints Commission, which initiated a year-long investigation by the Kent Constabulary that produced a 400 page report which found that, while there were areas of the investigations that were of mediocre quality, there was not "any evidence to support allegations of racist conduct by police officers."

But that did not resolve the matter. Instead, with the advent of the Labor government, a new inquiry was inaugurated under the direction of Sir William Macpherson, a retired High Court judge, which was intended to make recommendations concerning how the police should handle racially motivated crimes.

Now, the "terms of reference" for the inquiry: "To inquire into the matters arising from the death of Stephen Lawrence on 22 April 1993 to date, in order particularly to identify the lessons to be learned for the investigation and prosecution of racially motivated crimes," implied an impartial investigation. But the hysteria that gave rise to it was not driven by a desire for an impartial inquiry, but for a finding that the police were racist.

Their problem was that, after a year-long investigation, like the Kent Constabulary, they could find no direct evidence of it, either in organization policy or in police behavior.

But they were going to find the police force guilty of racism nonetheless. That was where the term "institutional racism," a term they derived from the American black power activist Stokely Carmichael, came in.

Their definition, as amended by the efforts of Sir Paul:

The collective failure of an organisation to provide an appropriate and professional service to people because of their colour, culture, or ethnic origin. It can be seen or detected in processes, attitudes and behaviour which amount to discrimination through unwitting prejudice, ignorance, thoughtlessness and racist stereotyping which disadvantage minority ethnic people.

It is obvious that the key term is "because of." Notice that there is nothing in this causality that must be directly observed or is overt or conscious. How are they going to identify it?

Two ways. First off, they didn't have to. They could farm it out. To whom? Well, anybody, as it turns out. They employed various equivalent formulations, one being a definition by the Association of Chief Police Officers: "any incident which included an allegation of racial motivation made by any person. Thus, their definition of racism required no support, but only an accusation.

This left them all the leeway they needed. Something is racist if they, or anybody, says it is racist, and especially if it is perceived to be so by the "victim," who may be, of course, defined as a victim only by this imputation of racism itself.

But we make things too easy on ourselves if we suppose they justified their charges solely on this linguistic contrivance. The apparent affect in their report indicates that they believed their claim. I think we should take them at their word for that. When they charged racism, we shall assume, they meant something.

But what could it be? The Kent Constabulary, after a full year of investigation had found no racism. They, themselves, had found no racism in the policies of the police, nor in the behavior of police members. Yet they found racism. How did they do that?

That is the point I will address in Part Three of this essay.

Note: In my analysis of the Macpherson hearing, I have made extensive use of Racist Murder and Pressure Group Politics by Norman Denis, George Erdos, and Ahmed Al-Shahi (London: Institute for the Study of Civil Society, 2000). It is a superb book.