A Conservative Obligation: David Lean’s The Sound Barrier

From the desk of Thomas F. Bertonneau on Thu, 2010-07-01 21:39

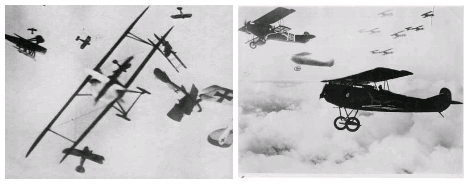

Cinema means movement, hence the nickname, “motion pictures.” Right from its beginning in Eadweard Muybridge’s stop-motion films of horses – and of male and female nudes – the “movie camera” has demonstrated understandable fondness for things robustly animate, the more impressive the hyper-kinesis the better. Visiting aliens might be excused for thinking that the main subjects of film are the galloping horse, the steam locomotive, the automobile, and the flying machine. A remarkable Georges Méliès (1861-1936) production based loosely on Jules Verne, Le voyage à travers l’impossible (1904), deploys all of these modes of transportation in a mélange of mechanical and transcontinental fantasies in the auteur’s inimitable style. [Clip] In the aftermath of “The Great War” (1914-1918), filmmakers began to see the possibility of theatrical spectacle in aeronautics. For Wings (1927), director William Wellman (1896-1975) put together an air force in San Antonio, Texas, that must have rivaled the United States Army Air Corps of the time; he installed cameras in a variety of “platform” aircraft and shot “dog fights” (below) of astonishing realism. [Clip]

Wellman’s air combat epic inaugurated the cinematic tradition of the aerial ballet, featuring the machines more than it did the pilots. The film itself exalted in the technical audacity that it celebrated, utilizing color sequences, an early version of widescreen, and elements of synchronized sound.

Howard Hughes followed up Wellman’s commercial success with Hell’s Angels, begun as a “silent” in 1928 and finished as a “talkie” in 1930, with James Whale as substitute director for the two previous executive talents who came into conflict with the quirky producer. Like Wellman, Hughes assembled his own air force – in Ventura County, in Southern California – in order extravagantly to restage the large-scale aerial confrontations of 1917 and 1918. [Clip] Like Wings, Hell’s Angels used color processing and other technical innovations; the film’s miniature work for the Zeppelin raid over London remains a model of special effects, far more convincing than any CGI cartoon. In one scene, to lighten the stricken airship, the Prussian Luftschiffkomandant gives the order to half of his crew to jump through the bomb bay to their deaths. [Clip]

Both Wellman and Hughes were accomplished pilots, Wellman having flown in combat in the War. Hughes, an aircraft designer and record-setter, remained keenly aware of the esthetic element in aerodynamic form. His H-1 Racer of 1935 (below) makes the point. The H-1 is said to have inspired the Mitsubishi design firm in its “Zero” model fighter-interceptor of the Pacific War.

Images of futuristic air warfare dominate the Alexander Korda / H. G. Wells film Things to Come (1936), which ends with the launching of the first lunar expedition. The black-finished single-seater flown by Raymond Massey, as protagonist John Cabal, still looks rakishly ultramodern in its lines, seventy-five years after Frank Wells, the novelist’s brother, dreamed it up. The film also gives us a fleet of gigantic flying wings. [Clip] Warner Brothers put Errol Flynn into the air twice beginning in the late 1930s, first in The Dawn Patrol (1938), directed by Edmund Goulding (the original director of Hell’s Angels) and again in Dive Bomber (1941), directed in color by Michael Curtiz (1886-1962) and starring, rather more than Flynn or Fred MacMurray, an array of naval aircraft, sleek or large, such as the Vought SB2U Vindicator and the Consolidated Aircraft PBY5 Catalina. [Clip]

The war years saw many aviation films, including Swedish director Hasse Ekman’s Första Divisionen (1941), about organizing the Swedish Air Force (Flygvapnet) to respond to the Soviet and Nazi threats. Events in such films conspire to put men under pressure; the men must match themselves to the demanding machines, placing their family and social lives second.

The real interest in aviation cinema lies, however, not in the perfunctory drama, but in the forms and movements of the aircraft themselves and – if one were to place such films in their historical sequence – in the urgent perfection of those forms towards the increasingly abstract. Oswald Spengler writes, in The Decline of the West Volume II (1922), of “Faustian Technics.” “The intoxicated soul wills to fly above space and Time,” Spengler asserts, while “an ineffable longing tempts him to indefinable horizons.” According to Spengler, “the machines become in their forms less and ever less human, more ascetic, mystic, esoteric” until “they weave the earth over with an infinite web of subtle forces, currents, and tensions.” One remarks an element of ambiguity in Spengler’s assessment. Spengler admires the machines, but he discerns their tendency to absorb and dehumanize their makers and users. Spengler perceives that machines might function on one level while signifying on quite another, often with rich connotation. The cruciform-dynamic shape of the standard airplane links its powered ascent with the spires of the great Cathedrals of the Gothic Age. The machine, in the metaphor, “vaults the heavens.”

One filmmaker who understood both the esthetic and spiritual implications of high-speed flight and the powerful allure over men of “subtle forces, currents, and tensions” was, perhaps unpredictably at the time, David Lean (1908-1991), known in his early career, in the 1940s, for spirited cinema-adaptations of Charles Dickens and in later career for lyric-heroic films like Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and Doctor Zhivago (1965) that tackled historical topics on the largest scale. In 1952 Lean directed what I nominate as the finest aviation film ever, the brilliantly understated story of British test pilots in the first decade of reaction propulsion, The Sound Barrier. Lean’s well-paced film does two things at once, among many others, which might strike one as contradictory or irreconcilable.

The Sound Barrier celebrates in beautifully day-lit black-and-white cinematography the angular sheet-metal poetry of the sweptwing, jet-powered planform and it pays gentle respect to the pastoral beauty of the English countryside, where the testing of the aircraft takes place. The setting – Hampshire’s rolling hills and farmlands, and its towns of medieval architecture – brings to mind the Kentshire landscapes of Michael Powell’s A Canterbury Tale (1944). Lean’s film also reminds viewers that, even in 1950, building the aircraft prototypes remained a matter of handicraft exercised by skilled journeymen.

With a backward glance to the last year of the war, The Sound Barrier begins with RAF flight lieutenant Philip Peel (John Justin) taking his clipped-wing Spitfire into a steep dive from altitude. [Clip] The Spitfire’s rapidly increasing airspeed generates severe buffeting, with Peel only barely regaining control so as to prevent the airframe from shaking itself to pieces. Many World War Two pilots reported this phenomenon, which killed some of them. Aeronautical engineers understood the basics: Speed equaling compression, a “barrier” of super-dense air begins to crowd and resist the leading edges of the wings and tail, rendering the control surfaces useless. Peel lands and reports the event to distracted fellow pilot Tony Garthwaite (Nigel Patrick). The film leaves Justin (below left) for a time to focus on Patrick (below center) who, as Garthwaite, screws up courage to ask his girlfriend (Ann Todd) to marry him. Todd (below right) plays the daughter of aircraft magnate and technical visionary John Ridgefield (Ralph Richardson).

The Ridgefield paterfamilias gives Garthwaite a privileged view of the latest project at the works: A turbojet engine on its static bed. [Clip] As Garthwaite watches with fascination, his bride already senses competition. With the war winding down, Susan’s father brings his son-in-law into the firm as chief test pilot.

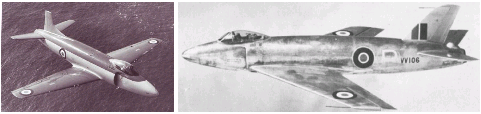

The opening titles of The Sound Barrier, following Peel’s desperate moment in the plummeting Spitfire, testify to the film’s consistent and studious visual focus, the sculptural artifact that is the fast jet. To a typically deft symphonic accompaniment by the redoubtable Malcolm Arnold (later reworked by the composer as an independent orchestral “rhapsody”) the credits list the actors and their roles. Then, in a gesture almost boyishly gleeful, the airplanes get their own headline, as though they were also characters in the story. But of course! The four types are: The DeHavilland Comet, the Supermarine Attacker (below left), the DeHavilland Vampire, and the Supermarine Swift (below right). An onscreen acknowledgment thanks the Society of British Aircraft Constructors and, by name, eight test pilots who flew for the film.

The British public knew well the Society, the sponsor-organizer of the popular Farnborough Airshow beginning in 1948. The annual displays at Farnborough supplied rich footage for British newsreels. [Clips from 1949, 1950, 1951, and 1952] As in the United States so, too, in Britain aircraft manufacturers revealed a plethora of new types every year. The newsreels make evident the intense public interest of the time in aerodynamics, as also in the arcing beauty of powered flight. The Sound Barrier draws some of its inspiration from the cinematic journalism-coverage of the Airshow.

The Sound Barrier begins with Peel’s Spitfire above the English Channel at Dover. It ends with a glimpse of the distant heavens. These bracketing images define the metaphysical trajectory of the story, very much in the mode per aspera ad astra. Lean conveys the idea that technical progress itself accelerates by the simple expedient of sequencing the types. The Attacker, a jet fighter for the Royal Navy first flown in 1946, incorporated the laminar-flow wing originally intended by Supermarine for its piston-engine successor to the Spitfire, the Spiteful. The twin-boomed DeHavilland Vampire followed into service Britain’s first jet fighter, the Gloster Meteor, the only allied jet aircraft to serve operationally during World War Two. The Vampire (below), which like the Attacker was a straight-wing airplane, only just missed the war. In the 1950s it flew with dozens of air forces around the world.

In two extended flying sequences the Attacker, despite its conventional planform, looks swift and agile. Cameraman Jack Hildyard (1908-1990) – he would work with Lean again on The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) – captures the three-dimensional aerobatics in what is arguably the best flight-related footage ever filmed.

The Sound Barrier is not a war movie although it is a story of conflicts. Hildyard’s aerobatic sequences, synchronized perfectly in finished form with Arnold’s deft score, emphasize the solitude and lyricism of airframe testing. Another acoustic element of the film deserves mention: The sound of the jet engines – which the Foley artist on Lean’s post-production team makes to resemble now an equine whinny, now the rolling thunder, and now the screech of the banshee, with many subtle shadings in between – belongs to the galvanizing sensory reality of reaction propulsion. Arnold orchestrates with his usual canniness, showcasing instruments of high register, like the flutes and piccolos, in the fabric of whose intertwining timbres the voice of the engines fits like one of the family.

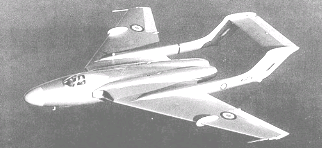

Two actual aviation events dogged The Sound Barrier in the year of its release. The Americans had broken the proverbial “barrier” in level flight in 1947 with the Bell X-1 rocket plane, but the United States Air Force kept the feat secret until five years later, when the British were still only diving their aircraft past Mach One. The American revelation, coming when the film debuted, stole some of Lean’s thunder. Then at Farnborough in 1952, test pilot John D. Derry’s DeHavilland DH.110 fighter plane (below) – a swept wing evolution of the Vampire – broke up in flight killing Derry and co-pilot observer Anthony Richards. [Clip] Seconds before the disaster Derry had dived his machine through Mach One.

Twenty-nine spectators also perished when heavy debris from the mid-air disintegration smashed down on the crowd. Fellow test pilot Neville Duke almost immediately took to the air in a prototype Hawker Hunter, flying in which he exceeded Mach One in a dive. Speaking of supersonic flight regimes in the early days, the dean of British test pilots Eric Brown once said in an interview, “We realized that this was going to be a very costly field.”

Death in the air belongs to the thematics of Lean’s film, which references the DH.110 crash at Farnborough. On the day after their nuptials the newlywed Garthwaites witness the death of Susan’s diffident younger brother Christopher (Denholm Elliot) when he tries to fly solo, under pressure from his father, in a light plane. The daughter holds her brother’s death against the father whom she comes to regard as heartless and cold. Christopher’s plane need not have caught fire on hitting the ground, Ridgefield remarks to Tony after the funeral, “if only he had switched off.” The death was pilot error, the parent implies. Susan glares silently. Garthwaite becomes the substitute son, bonding closely with Ridgefield, whose laconic determination he respects and comes increasingly to share. He shrugs off danger with the casual words, “Piece of cake.” Susan’s worries put a strain on the marriage, especially when she learns that she is pregnant.

The Sound Barrier realistically shows the sexual division in these matters. In their pioneering ambition and unsentimental commitment to technical challenge men willingly risk their lives in extreme situations. The uxor, averse to the hard metallic world of the machines, lives moodily, jealous of the man’s preoccupation, and always expecting the worst.

Lean leads viewers on for some time into seeing it from Susan’s viewpoint. (She has a viewpoint, the feminine one, after all.) Even Ridgefield’s chief engineer Will Sparks (Joseph Tomelty) begins to think his boss inhuman. Aided immensely by Richardson’s representation, however, the director gradually reveals Ridgefield, the industrialist, as a hero in his own right – a necessary man seeing to a necessary job. Garthwaite asks Sparks, “Seriously, apart from the buffeting, and the heavy controls, and the wanging and banging, and other little problems, what does happen to an aeroplane at the speed of sound?” Sparks replies, “I don’t know, and shall I tell you something, Tony – no one else does either.” Ridgefield tells Susan that there is “a whole new world with speeds of fifteen hundred and two thousand miles per hour within the grasp of man.” He regards his son-in-law as the fellow who will grasp that world.

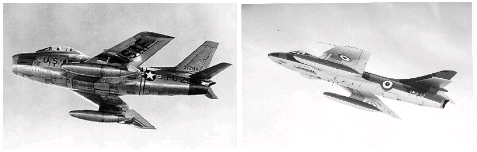

Garthwaite will “buy it” flying in the “Prometheus,” actually the Supermarine Swift. Even more than the Attacker sequences, the “Prometheus” sequences constitute the scenic highpoint of The Sound Barrier. Whereas the Attacker wears its Royal Navy livery, Lean puts the Swift in clean metal finish, giving accent to its pleasing lines. The Swift belongs to the beautiful late-1940s generation of jet fighters. Like its contemporaries the North American F-86 Sabre Jet (below left) and the Hawker Hunter (below right), the Swift possessed elegance of shape regrettably not achieved in the later generations of fighter aircraft. In the “Prometheus” sequences, too, Lean exploits the seeming contrast between the technical sophistication of the machine and the rustic beauty of the English countryside. For Lean, the machine is not inimical to the natural surroundings. A farmer’s acre is already an alteration of nature, indeed. Viewers also see the tiny silver fleck of the Swift against mountainous clouds in a vast sky, a reminder that nature still towers over man.

Hildyard filmed the runway scenes at RAF Chilbolton Aerodrome, Nether Wallop, in Hampshire. [Clip] When the Swift leaps into the air, the setting is that of “England’s fields and pastures green,” to quote from William Blake’s Milton. Indeed, the impulse to beat the “barrier” is Lean’s version of the Blakean “mental fight,” with the airplane the Blakean “chariot of fire.” Only the most careful matching of mind and machine will master the physical chaos at Mach One. When Garthwaite crashes, leaving only an infernal crater in the gentle landscape, the job falls to his old friend Peel, now also on Ridgefield’s payroll, to continue testing the type. The story began with Peel, struggling to regain control over his Spitfire. On landing, he told Garthwaite that, if only he had borrowed the courage to reverse the controls by “pushing the stick forward,” he might have mastered his dive completely. He had kept his neck by pure luck.

At the critical moment in his own trials with the “Prometheus,” while hurtling crazily toward the farmlands from forty thousand feet, Peel finds this courage and saves himself. The sonic “boom” rattles the windows in Ridgefield’s office at the works.

Susan comes to understand her father and belatedly her deceased husband. She brings her son, born an orphan, to live with Ridgefield in the old manor. Ridgefield for his part feels his unbearable loneliness somewhat lightened. Lean spotlights Peel’s loneliness, too, in a remarkable post-flight scene. His wife, Jess, has no notion of what Peel has just done. She prattles about a new coat that she has just bought, wondering whether the color complements her hair. As Peel seats himself, hands shaking, he is laughing and sobbing at the same time. There is a reconciliatory conversation between Susan and Ridgefield in which the two of them mutually acknowledge the obligation of those who can imagine new things in light of their “vision” to do so. The film closes on the image of a new delta-wing design, in model, hanging from the ceiling next to Ridgefield’s telescope. As Arnold’s “barrier” theme swells up and out, the sleek shape points like an arrow at the field of stars.

No other aviation film achieves the seriousness or the lyricism of The Sound Barrier (renamed Breaking the Sound Barrier for its American distribution). Anthony Mann’s Strategic Air Command (1955), starring Jimmy Stewart, with camera work aloft by the legendary Paul Mantz, lapses entirely into insipidity when it shifts from the gigantic bombers – the Convair B-36 Peacemaker and the Boeing B-47 Stratojet – to the marital and social problems faced by Air Force newlyweds Stewart and June Allison. The aerial sequences are impressive, including a round trip by B-36 from Texas to Alaska and back. [Clip] The footage proves that the Peacemaker, a ten-engine monstrosity, could actually be graceful in the air. Otherwise SAC is a cold-war recruiting stunt with extended courtesy in the production thanks to Stewart’s wartime friend Air Force General Curtis Lemay.

Philip Kaufman’s film The Right Stuff (1983), based on Tom Wolfe’s book of the same name, concentrates on NASA’s Mercury Program of the early 1960s, with its effort to put an American astronaut in orbit. In its Charles “Chuck” Yeager subplot, however, The Right Stuff really is an aviation film, of considerable merit. Yeager’s attempt to push his F-104 Starfighter vertically to the edge of space is an essential expression of “Faustian Man,” with a American Southwest accent. [Clip] Nevertheless, Kaufman never achieves the subtlety of Lean. Maybe it is the garishness of Kaufman’s color. Lean’s black-and-white approach does greater justice both to the machines and to the Hampshire setting.

Knowledge of flight and airplanes belongs to masculine lore, nowadays too little cultivated. I owe much of my own indoctrination in such matters to my great uncle on my mother’s side, David van Westen (my “Dutch Uncle”). “Uncle Dave,” born around 1920 and still living, was a “Norcrafter,” an employee of Northrop Aviation, in the 1940s and 50s. He worked on many Northrop projects including the original “Flying Wing,” the XB-35. Van Westen preserved a collection of Flying Aces (below), a pulp magazine of the 1930s and 40s specializing in military aviation stories. I read every issue on generous loan.

I also owe a good deal of what I know about flight and airplanes to my older brother, Dan (born 1936) – an aerospace engineer with stints at Lockheed, where he redesigned the ejection seat of the F-104, and at North American, where he worked on the J-5 engine of the Saturn V Moon Rocket at the managerial level.

My male students at SUNY Oswego, where I teach in the English Department, know almost nothing about flight or airplanes. They have never read Pylon (1935) by William Faulkner or Pilote de Guerre (1942) by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry and they have never heard of Flying Aces or the Supermarine Swift or the Sabre Jet. This deficiency belongs to their general spiritual emasculation in a world dominated by sensitivity, emotions, free-association, “smiley faces,” “fairness,” “comfort food,” soccer leagues for girls, “women’s studies,” “bad hair days,” “offense” and other specifically female institutions, conspiracies, and phenomena. In a Spenglerian mood, I say that fathers should instill in their sons careful appreciation for powerful, dangerous, and extravagant machines.

I am happy to stand

Submitted by Thomas F. Bertonneau on Thu, 2010-07-08 08:21.

I am happy to stand corrected.

British obfuscation of the historical record

Submitted by roughdoggo on Wed, 2010-07-07 01:39.

Dear Professor Bertonneau,

There's something odd about your statement that "Americans had broken the proverbial 'barrier' in level flight in 1947 with the Bell X-1 rocket plane, but the United States Air Force kept the feat secret until five years later, ... The American revelation, coming when the film debuted, stole some of Lean’s thunder".

In fact, that statement is completely wrong: a cursory search through the archive of the New York Times online shows any number of reports about Chuck Yeager's supersonic flights for the period 1947-51. Lean's "thunder" was stolen years before his film was released!

There was no long-term veil of secrecy regarding the Bell X-1 flight: word was out in the papers less than 2 months after the event. The Collier Trophy was (publicly) given to Yeager and two others for the feat in 1948. This not to mention the Mackay trophy given to Yeager in the same year for the same deed.

It appears that certain Brits (aka "sore losers"), riled at the loss of the supersonic prize, determined to "set the record crooked" in the minds of the British hoi polloi through the medium of film.

Yeager refers to his own exasperation regarding this bit of misinformation in his autobiography, given that he was confronted over the years with the ignorance of many from across the Pond, who – taking fantasy for fact – let it be known to him that they "knew" that he had been preempted in supersonic flight by UK fliers!

@KO @mpresley

Submitted by Thomas F. Bertonneau on Sun, 2010-07-04 12:17.

The discussion of the model airplane kits reminds me that the hobby of assembling them actually ran afoul of the nanny state, in its early form, when I was in high school in the early 1970s in California. The model airplane kits were of pre-molded plastic and one assembled them with a special glue containing toluene. Alas, addicts of intoxication discovered that they get a “high” from sniffing the glue. Naturally, the state safety and health bureaucracy got involved, reclassifying the glue as a special substance. A kid could still buy the model airplane, but anyone under eighteen had to have his parents present to buy the glue. A type of “safe” non-toluene glue came on the market, but its adhesive power was null and it would not reliably join the plastic sections.

The topic might even have an Aristotelian implication. In The Poetics, Aristotle declares that Man is the most mimetic of animals, meaning that the human being is at once highly prone to imitate the actions and attitudes of others and to enjoy imitations of things, like painting and statues and dramas representing large actions. Building, painting, and admitting the model airplanes added up to genuine esthetic instruction for boys.

A quick search of the Internet reveals that the kits are still available, but they seem to be marketed at people of my age. That would suggest that the hobby has disappeared among its natural clientele of adolescent boys.

I agree with KO that the Airfix kits (from Britain) were satisfyingly fine and detailed, as were the “Italkit” models (from Italy). But the Revell and Monogram kits were far more available. One could buy them in supermarkets and drug stores.

I too remember the pleasure of the model airplane auto da fé, in which broken or misshapen or badly assembled items were offered on a pyre or by firecrackers to Mars or Thor or – but who is the Patron Saint of Model Airplane Kits?

It's all true:

Submitted by mpresley on Sun, 2010-07-04 16:33.

The model airplane kits were of pre-molded plastic and one assembled them with a special glue containing toluene.

The toluene (or so I remember being told) did not actually "glue" the parts, but melted the styrene plastic into almost a weld. Testors was the best, but there was another brand (don't remember the name) that was never any good. As Dr. Bertonneau retells, it all went south once a few marginal characters figured out they could get "high" sniffing the stuff, and once the government got involved. Once the glue was outlawed, the illicit users just switched to paint thinner, and the rest of us got other hobbies.

On an aside, in high school I actually knew a kid who spent summer vacation in the woods inhaling the stuff. He was never the same. His parents were university profs, so he probably had a lot of "normal" potential. Who knows? Anyhow, he pretty much turned into a zombie, mentally. But that's not all bad, because now he's got a TV show:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TrcM5exDxcc

@Traveller, @Kappert, @Mpresley

Submitted by Thomas F. Bertonneau on Sat, 2010-07-03 15:01.

Traveller, I take Kappert to be referring to the early transatlantic air routes, many of which were served by seaplanes and flying boats. Unlike the steerage conditions that prevail on the modern “efficient” airliner, those associated with mid-Twentieth Century air travel were elegant and sometimes luxurious. Even when I started flying – in college, when cheap fares made it possible to fly from Los Angeles to San Francisco on a weekend – flying still possessed a certain dignity, which it has long since lost. The airport regime and the onboard atmosphere are now those of a tin-pot police state.

Mpresley reminds us that, in the USA anyway, the plastic model airplane kit was an important recreation for boys. The kits required careful assembly and painting and taught the builder a good deal about the structure of the aircraft. This must have been a phenomenon in Europe, too, because many of the kits that I built were imports from Britain and Italy. Indeed, the most detailed and finely molded kits came from Italy. A brochure generally accompanied the kit that gave the history and specification of the machine. It was an edifying recreation in all senses, from hand-eye coordination, to history, to esthetics. And it was exclusively masculine. Girls did not build model airplane kits.

Airfix

Submitted by KO on Sat, 2010-07-03 16:11.

Greetings and thanks to Dr. Bertonneau for this most delightful of essays. I will hazard a scattering of recommendations: if you are in Florida, plan to spend a couple of days visiting Cape Canaveral and touring the early rocket sites. For movies, The Bridges at Toko Ri is a good study of Navy pilots. Twelve O' Clock High is a magnificent, unsurpassed study of Army pilots. Tom Wolfe's essay "Jousting with Sam and Charlie" is an excellent study of carrier pilots and a precursor to The Right Stuff. MPresley: I preferred Airfix to Revell, slightly cheaper and I thought they fit together better. We carefully assembled and painted them, displayed them on shelves and hung them from the ceiling. I preferred WWI and WWII aircraft, but my uncle (3 tours of Vietnam in 52's and Phantoms) had a grand set of jet aircraft including the memorable B-58.

I don't think my friends and I were unique in blowing up and burning the results of our handiwork, perhaps in an unconscious sacrifice to the God of Aviation.

If you are near the Cape in FL

Submitted by Poker Player on Tue, 2010-07-06 02:15.

Drive on over to NAS Pensacola and visit the Naval Air Museum.

Yes indeed..

Submitted by mpresley on Sat, 2010-07-03 19:42.

KO writes:I preferred Airfix to Revell, slightly cheaper and I thought they fit together better.

The hardest were the balsa models. WW1 planes were a bit complicated because you had to get the rigging between wings just right. I think the imported models that the prof talks about were beyond my financial means. I remember when the old man (a veteran of the 14th Air Force, Indo-China theatre under Claire Chennault) brought home a B-24 model. The thing took us forever to build. What a beauty! Guys who actually flew those things have my respect for it.

Once, the old man was shot in the hand by ground fire. He refused a Purple Heart because he'd seen his buddies in worse shape, or dead, and would have been embarrassed to wear it as the wound was minor. Not like John Kerry. But that's how it was, back then. Men often had respect, honor, and a sense of duty.

@mpresley

Submitted by KO on Sat, 2010-07-03 21:32.

Even the plastic biplanes presented the challenge of wanting to collapse while the glue was still wet. I never dared to attempt a paper and balsa model.

I built the Airfix B-24, but it didn't look so great because the brown paint wouldn't stay mixed. This was more than 30 years ago. I also built the Airfix B-17, B-25, P-47, P-51, P-38, and PBY. I think the B-26 and P-40 were Revell.

I just checked the Airfix website. I think the Me-109 cost 49 cents when I bought it. It is now $6.99. Less than the cost of a movie, though!

The great line in The Bridges at Toko Ri: "Where do we get such men?" Happy 4th!

Atlantic vessels?

Submitted by mpresley on Sat, 2010-07-03 14:59.

Not as strange as it sounds. In fact, I get the distinct feeling, when considering our judges, legislators, and the executive, that the remaining citizenry must be arranging deck chairs on the SS (Ship of State) Titanic, in anticipation of whatever might come next.

@ kappert

Submitted by traveller on Sat, 2010-07-03 10:25.

Atlantic vessels?

really nice

Submitted by kappert on Sat, 2010-07-03 07:59.

That's a good idea to rewoke the first steps of an industry. Please continue with civil aeroplanes, Atlantic vessels, and early space conquests.

Are you kidding?

Submitted by mpresley on Fri, 2010-07-02 21:32.

My male students at SUNY Oswego, where I teach in the English Department, know almost nothing about flight or airplanes...

When I was younger, probably too long ago, airplanes and flight were a top theme of kiddom--not just for me, but all boys. When we had some money we bought the Revell models and staged pretend aerial duels. We knew all the Aces. Men like Jack Northrop and especially Kelly Johnson were the heroes of our imagination. In those days, Kelly and his engineers could come up with, oh, I don't know, maybe an SR-71 and have it flying over the Soviet Union within a few years. Today, it's been over five years and the Air Force can't figure out where to buy their tankers.