“Les Troyens” by Hector Berlioz: Heroic Opera in an Un-Heroic Age

From the desk of Thomas F. Bertonneau on Thu, 2010-04-22 05:35

As reporter Hugh Schofield wrote at the time, the plan to move Berlioz’ mortal remains “met with unexpectedly harsh opposition from many of the composer’s own fans, as well as from critics who say Berlioz was a right-winger with no place in France’s Republican Valhalla.” Schofield quotes Berlioz biographer Joël-Marie Fauquet as asserting in an editorial in Le Monde: “The Berlioz who invented the modern orchestra also showed himself in his life to be an ardent reactionary.” A committee supervising the Bicentenary celebrations referred the matter to then Président Jacques Chirac, who by his silence and inaction sided with the Fauquet position. Berlioz remained in the ground at Montmartre.

I. Connoisseurs of Berlioz know him as a profoundly literate man of broad yet discerning opinion (he was a writer as well as a composer), so they know his puritanical detractors as, in like degree, illiterate. The accurate description of Berlioz’ attitude toward the tumult of French politics in the mid-Nineteenth Century is that he had taught himself by his early thirties to disdain the recurrent fervor of an indefinite succession of soi-disant revolutions punctuated by bouts of sclerotic dirigisme. Berlioz despised Napoleon III, who summarized the trend, as a cultureless farceur in uniform. Berlioz’ judgment of the governing classes thus hardly qualifies him as reactionary although political agitation for radical causes and revolutionary movements against the traditional dispensation does, as practiced by the Left, qualify one as reactionary. Near the end of his life, indeed, Berlioz described his attitude toward politics and politicians in a letter to Princess Carolyne Sayn-Wittgenstein, a one-time paramour and late-in-life confidant: “Those pathetic little gangsters known as great men rouse me only to disgust – Caesar, Augustus, Antony, Alexander, Peter [the Great] and all the rest of those glorified brigands.”

Musicologist Martin Cooper has written in French Music from the Death of Berlioz to the Death of Fauré (1951) that Berlioz, like Baudelaire, sought refuge from secular disappointment in his “private world” of artistic endeavor. Berlioz lived in the French polity, right in its metropolis, perforce but he sought no redemption in politics; he necessarily communicated with ministers of state and even kings and emperors, as did Beethoven in Austria and Dmitri Shostakovich in the Soviet Union – that is to say with reluctance and distaste. The composer’s characterization of Caesar and Augustus as “brigands” illuminates the argument of Les Troyens. Berlioz’ opera declares Fate and Empire to be, if not outright delusions, then derailments of constructive life, inimical both to private happiness and to love. The composer’s first important work, the Symphonie fantastique (1830), is a unified five-moment orchestral composition on the topics of love and betrayal. His final and greatest opus, Les Troyens, is a unified five-act opera on the same two topics, based on Virgil’s incomplete Latin epic, the Aeneid.

Les Troyens might well be said to objectify what in the Symphony fantastique remains subjective – the sacredness of privacy and intimacy and the wretchedness of political schemes that subordinate the human to abstract designs. The opera’s two female protagonists, Cassandra and Dido, replace the single male protagonist of the Symphonie fantastique’s notorious program.

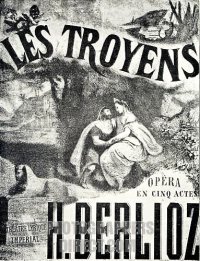

Berlioz wrote in his Memoirs: “I had conceived of a vast opera on the Shakespearean plan, based on the second and fourth books of the Aeneid.” Princess Carolyne urged Berlioz in 1856 to write the libretto, which he completed in 1858. He read it privately to friends in various salons until rumors of its existence began to circulate in public. The Opéra showed no interest but gradually Berlioz convinced his acquaintance Léon Carvalho, director of the Théatre-Lyrique, to back the effort. A smaller venue than the Opéra, the Théatre-Lyrique could not adequately mount the grand tableaux indicated by the score, which Berlioz brought to completion in all its aspects in 1860. The composer and playwright bowed to practicality. He not only agreed to jettison the first two acts but also to adapt the remainder to Carvalho’s smaller cast and facilities. The excised acts (I and II) together constituted Part I of the opera, La Prise de Troie, which the composer would never see staged and which no company would tackle until an ambitious production in Karlsruhe in 1897.

The remaining three acts (III, IV, and V) became Les Troyens à Carthage, with a summary prologue devised by Berlioz for the occasion to give the audience some sense of the omitted action. The disruptive, inhuman Déstin of Berlioz’ scenario, a motif that Berlioz borrows from Virgil’s text, seemed to fall on the production like an Olympian curse, with every conceivable annoyance conspiring with every other to force the author into further artistic compromise. The fire marshal of Paris forbade the extras from carrying torches in the pantomime to accompany the Chasse royale et orage, making the effect ridiculous; the same interlude required a set-alteration that the stagehands made with habitual agonizing slowness, necessitating the insertion of a dramatically awkward half-hour intermission.

II. Carvalho argued with Berlioz about the diction of his libretto: “There’s a word in the prologue that worries me… Triomphaux”; “It’s the plural,” said Berlioz, “of triomphal, as chevaux is of cheval, originaux of original, madrigaux of madrigal, [and] municipaux of municipal.” The pettiness and irrelevance of the objections irritated and depressed the composer, even though he was used to such meddling after a lifetime of experience in getting his music performed. By a miracle, the November to December 1863 run of Les Troyens turned a small profit, but remaining nervous, Carvalho closed down the production after twenty-two performances. In his study of The Sonata principle (1962), the late Wilfrid Mellers puts his finger on the real disconnection between Les Troyens and its mid-Nineteenth Century French public – or possibly any public of any time:

Les Troyens…is an idealized vision of a new heroic civilization: or rather of the old world, and the old technique born anew. This was no puerile utopia. Dido is a heroic figure, but also a woman, with human passions and frailties. In Berlioz’s imaginary aristocracy, people, like Dido, would still love, suffer, and die, as they have always done; but human life would acquire once more the dignity and sanctity of the heroic age.

Mellers says that Les Troyens expresses Berlioz’ “growing sense of disparity between the ideal and the real,” a sense that the composer shared with the author of the Aeneid. David Cairns remarks in his introduction to the Berlioz’ Memoirs that the composer shared with Virgil “fear of the collapse of civilization as they knew it.” Both Mellers and Cairns could well be quoting the man himself. Berlioz once wrote: “The mass of the Paris public [regards] all music that deviates from the narrow path where the makers of opéras-comiques toil and spin… the music of a lunatic.” The Second Empire struck Berlioz as an age of insipidity, without seriousness, launched on a course – like Faust in his earlier opera La Damnation de Faust (1846) – towards the abyss. Less than a year after Berlioz’ death from cancer, the Second Empire would disintegrate under the Prussian advance, giving birth to yet another republic.

An editorial cartoon from the time of Les Troyens à Carthage at the Théatre-Lyrique strikingly corroborates Berlioz’ sense of his era, both musically and politically. The cartoonist, “Charivari,” depicts Greek soldiers with their hands covering their ears running away from a masonry wall behind which is seated an orchestra; above the orchestra a banner flies, which reads, “Partition des Troyens,” or “The score of Les Troyens.” The caption says: “Comme quoi les Grecs auraient certainement levé le siege devant Troie si les Troyens avaient eu la partition de M. Berlioz en temps utile.” (“If only the Trojans had armed themselves with Mr. Berlioz’ score, they would certainly have repelled the Greek attack.”) The sensibility of the Second Empire inclined to the buffoonery of Jacques Offenbach’s Belle Hélène and Orphée aux enfers; it preferred Italian bel canto opera and Gounod, but Berlioz it could not understand.

On the other hand, one might interpret the cartoon as prophecy-in-spite-of-itself, heralding the humiliation at Sedan and the Commune.

Productions of Les Troyens happened sporadically in the last third of the Nineteenth Century, mostly in Germany, and the first two thirds of the Twentieth Century, mostly in Great Britain. The first recording – of Les Troyens à Carthage only – came about in 1952 under the direction of Hermann Scherchen. Famously, Colin Davis led performances at Covent Garden in 1969, recording the work without cuts for Philips a year later. James Levine headed an important mounting of the work at the Metropolitan Opera in 1984, with Jessie Norman taking the roles both of Cassandra and Dido. The Covent Garden and Met performances having dispelled the aura of a logistically impossible work, Les Troyens has since appeared less infrequently without quite establishing itself.

III. As the bicentenary of Berlioz’ birth approached, productions of Les Troyens fairly proliferated, with at least six in 2003 alone. A kind of performing tradition had settled in, going back to the original Théatre-Lyrique design, with its monumental scenic decor, faux-antique costumes, and massive stage action – even though the prescribed massiveness was limited by the original venue. Typical of these more or less traditional productions of Les Troyens was the one under Levine in 1984, broadcast on television and preserved on DVD. The stage is large and the décor suitably archaic and massive; the costumes suggest Mediterranean antiquity. The audience even gets to see the notorious “Trojan Horse” being dragged through the gates in the background at the end of Act I. In the period that calls itself “postmodern,” of course, anything as literal as that would have to go.

The two recent undertakings of Les Troyens documented on DVD during the bicentennial – the Cambreling and Wernicke interpretation for the Salzburg Festival and Gardiner’s Théatre de Chatelet interpretation – are predictably quite different in style from the Levine Troyens of 1984, especially Cambreling’s version. Gardiner’s Chatelet Troyens thankfully avoids the worst excesses postmodern “director opera” and stands as a great musical performance, the equivalent of Davis’ Covent-Garden sally of 1969. Cambreling’s Troyens is another thing altogether – musically acceptable, but scenically inadequate – even to the point of being a deliberate betrayal of Berlioz. It is best to begin with (and dispose of) Cambreling.

We recall that when Cambreling’s Troyens was staged in Salzburg, critics attacked the performance for political or rather ideological reasons. Exactly why the politically correct critics attacked Cambreling and his set-designer Wernicke is hard to say, since it would be difficult to imagine a more politically correct, hence less faithful, staging of this colossus of sung theater, with its inescapable critique of any imperial ethos. Berlioz admired the operatic reformer Christoph Willibald Gluck (1714 – 1774). Traits that one associates with Gluck definitely inform Les Troyens. Nevertheless, Les Troyens is not Alceste or Iphigénie en Tauride. In Gluck, the action often comes to a halt so that characters might divulge their emotions, exquisitely refined, in extended arioso meditations. In Gluck again there is a good deal of sung exposition and little immediate action. These musical features of Gluck’s formula for music drama lend themselves to static blocking. But static blocking, when applied consistently, fits badly with Berlioz’ dramatic vision, which is altogether more dynamic than Gluck’s.

Things happen in Les Troyens. There are exits and entrances not only of individuals but also of crowds and armies. As the curtain goes up on Act I, the whole of Troy rushes from the city gates to the beach to celebrate the apparent departure of Les grecs. (Here is the Cambreling/Wernicke version of the scene.) At the end of the same act, the crowd drags the great wooden horse into the city, sealing the Trojan doom. Act III begins, as Berlioz wrote it, with a grand and extended ballet, which Wernicke, in the Salzburg production, entirely omits. Wernicke’s reduction of the scenery in all five acts to minimalist abstraction tells the audience everything about the nullity of postmodern esthetics but next to nothing about Berlioz’ Shakespearean theory of epic drama. For Wernicke – and it is clear from interviews that Cambreling agrees with his collaborator – all parties in Les Troyens, with the possible exception of Cassandra in Act I and II, are neurotic, vainglorious, and self-serving in their motivations. They squint at and shun one another.

As though anticipating the baseless charge of fascism while determining to validate it in advance, Wernicke dresses the Trojan soldiery in black military uniforms deliberately reminiscent of Nazi SS regalia. He has them carry American M-16 rifles instead of the expected antique armaments. Under Cambreling’s musical direction, the singers (who might well have other inclinations) interpret their parts stridently rather than beautifully, Cassandra’s terrific closing aria from Act I being deprived by the gesture of much of its pathos. Deborah Polaski, who sings both Cassandra in Part I and Dido in Part II, has a suitable voice for the Cassandra-role, but the directorial conception prevents her from acting with it as she might otherwise do.

Berlioz conceives of Carthage under Dido as a utopian project, with the people and their queen united to build up a new city free from the corruption of Tyre, whence Dido has fled after the murder of her husband by the usurper Pygmalion. As Berlioz writes his drama, the advent of the desperate Trojans on Tunisian shores and Dido’s betrayal in love by Aeneas disrupt the experiment in civic idealism. This is that “disparity between the real and the ideal” that Mellers remarks. Wernicke, for no discernible reason that might be related to Berlioz’ text, decided that the Carthaginians, far from being noble and idealistic, must be effete and cynical. He directs his actor-singers to comport themselves superciliously and nastily. He dresses them in black gowns and black business suits, adorning the women with elbow-length aquamarine gloves and built-up, atop-the-head, “beehive” coiffures, making them somewhat risibly resemble the fearsome housewives in Gary Larson’s “Far Side” cartoons.

In the Cambreling-Wernicke conception of the three Carthaginian acts, Dido and her court are people who sip champagne cocktails from long-stemmed glasses while reclining torpidly on Tyrian-purple, gold-fringed cushions. They all give the impression that the proceedings bore them to the point of terminal ennui. Cambreling speaks rightly when he says of Les Troyens, “Ce n’est pas une pièce très optimiste,” but rather one that emphasizes “la ruine, la fin d’un monde.” The destruction of Carthaginian happiness can only strike the audience as tragic, however, when Dido and her people possess admirable qualities. Tragedy lies in Dido’s very openness to love. The hymnal procession that opens Act III, on the refrain “Gloire à Didon,” emphasizes the caritas that animates the Tyrian colony on North African shores. (Here it is in an excerpt from the 1984 Levine production at the Met.) But for Cambreling and Wernicke, this procession becomes a parody of the modern – intolerably bourgeois – business meeting.

In their estimation of Aeneas, Cambreling and Wernicke come closer perhaps to Berlioz’ intention than in other matters, for while Aeneas is the hero of Part I he is effectively if not quite nominally the villain of Part II. If the image were not present, which it is because the production has been issued as a DVD, one might find many good things to say about the musical aspect of Cambreling’s interpretation. Critics have accused him of lacking fire but the criticism rings false. Opera being spectacle, however, and DVD being a visual medium, the production labors the music with a tendentious scene.

IV. Gardiner’s Chatelet Troyens operates at a far higher level intellectually, artistically, and musically than does its Salzburg counterpart although some “subversive” gestures from the postmodern playbook have found their way annoyingly into the mixture. Thus the Chatelet production takes the scenic design some distance towards postmodern abstraction, yet not nearly so far as Cambreling and Wernicke. The settings are recognizable. We even see Troy aflame in a brief transition from Act I to Act II. The Trojan soldiery wears what look like World War One British Army uniforms while the invading Greeks come clad in U.S. Army camouflage fatigues and carry, not M-16s, but Soviet-era AK-47s, which they aim savagely at the Trojan women at the conclusion of Act II. The North African half of the opera uses brilliant colors, retains the exotic ballet of Act IV, and emphasizes (rightly) the plan of Dido and the Carthaginians to establish a philosophical polity.

The audience sees, for example, models of the not-yet-completed acropolis of the city, and of the projected harbor, being consulted by surveyors and engineers. Heavily stylized, the scenery nevertheless exhibits some linkage to the performance-tradition, insofar as there is one, going back to the 1863 premiere. Some simple touches generate a wondrous effect, as when, during the Hymn to the Trojan Gods (“Dieux Protecteurs”) in Act I Gardiner puts a real sistrum, the antique instrument that Berlioz prescribed, onstage; or as when, at the end of Act V, Dido prepares for her suicidal death by unfurling a long magenta scarf down the monumental white steps that she has ascended. The scarf vividly symbolizes the fatal emotional wound that Aeneas has inflicted on Dido in the names of Fate, the Roman race-to-be, and Empire. The conversation-song of the Trojan sailors at the beginning of Act V, which Cambreling omits, reminds us that Berlioz thought of Les Troyens as Virgil seen through the dramaturgy of Shakespeare.

Musically, too, the Chatelet production repeatedly astonishes. Gardiner opts for two stunning divas, Anna Caterina Antonacci as Cassandra in Part I and Susan Graham as Dido in Part II. The elements come together for a powerful climax at the end of Act I when Cassandra sings her desperate heart out in prophesying the impending disaster in whose prediction the Trojan people refuse to believe; her desperate aria takes its place in counterpoint with the delirious joy of the Trojan March, the single unifying melodic motif of the two parts of the opera taken together.

Arrêtez! arrêtez! Oui, la flamme, la hache!

Fouillez le flanc du monstrueux cheval!

Laocoon!... les Grecs!... il cache

Un piège infernal...

Ma voix se perd!... plus d’espérance!

Vous êtes sans pitié, grands dieux,

Pour ce peuple en démence!

Ô digne emploi de la toute-puissance,

Le conduire à l’abîme en lui fermant les yeux!

(Elle écoute les derniers sons de la marche triomphale qu’on distingue encore et qui s’éteignent tout d’un coup.)

Ils entrent, c’en est fait, le destin tient sa proie!

Sœur d’Hector, va mourir sous les débris de Troie!

(Elle sort.)

During this scene, Berlioz instructs a small adjunct orchestra of brass players to accompany the people onstage. Gardiner deploys his musicians accordingly and in a scholarly coup realizes an opportunity to put on display the specialized Sax instruments prescribed by the composer in the score. Another terrific moment comes at the conclusion of the first North African act, when, on news that an enemy of Carthage advances with his armies on Dido’s city, the just-arrived Aeneas pledges his Trojans to fight alongside the Tyrian defenders. Tenor Gregory Kunde works hard to redeem Aeneas in Part II of the opera. He brings to bear his considerable thespian talent to make the character’s perfidy seem the result of confusion between the tug of love and the tug of duty. Together with Graham, Kunde delivers what is likely the most sublime performance ever of the third-act love-duet, in slow barcarolle rhythm, “Nuit d’ivress, nuit d’éxtase.”

Aeneas chooses duty (“Italie, Italie,” cry the unseen voices), but Berlioz chooses love and he clearly sides with Dido, as he did when he was twelve years old and studied the Aeneid under the tutelage of his Latinist father. Gardiner understands this whereas Cambreling and Wernicke manifestly do not – or understand it but cynically refuse to represent it. Gardiner brings his usual dedication to historically informed musical practice and period instrumentation to Les Troyens. One hardly notices it because the audible result so thoroughly convinces a listener of the interpretation’s rightness. Gardiner honorably serves Berlioz’s idea of the grand and the noble.

Berlioz added the last chapters of the Memoirs once the Théatre-Lyrique Troyens of 1863 had run its truncated course. “My career is over… I compose no more music, conduct no more concerts; no longer write prose or verse.” In pouring his lifeblood into Les Troyens, Berlioz says, “I did not take Latium.” He saw himself a failure. The prose gives the full sense of Berlioz late in life, as Cooper calls him, a broken man. He had outlived two wives. He would outlive his son. Friends were dying. He was dying. Berlioz recalls how, after Les Troyens debuted, strangers “often stopped [me] in the street… who wished to shake hands with me and thank me for having composed [my opera].” He wonders, leaving the question open, whether such spontaneous expressions of appreciation by ordinary lovers of music did not constitute sufficient compensation for the caustic hostility of the critics, “by whose hatred one can only feel honored, for it is the disdain of the whore for the honest woman.”

Thus does Berlioz the old man, eaten alive by stomach cancer and mocked by mediocrities, meditate on the world. While bitterness never represented the sum and total of Berlioz’ life, it dogged him. Berlioz did better in Germany than in his native country. At the ducal courts – in Weimar, for example – he found the positive response of highly trained musicians and sensitive audiences for which he had longed. Before the cult of Wagner in the German states came the cult of Berlioz – but no, never a “cult,” but rather a keen sense of something both new and beautiful and yet classical and traditional at the same time. The penultimate paragraph of the Memoirs epitomizes Berlioz’ hard-earned wisdom: “Love or music – which power can uplift man to the sublimest heights?” Berlioz answers his own question this way: “Love cannot give an idea of music; music can give an idea of love.” He concludes by questioning why anyone would want to separate music and love, for “they are the two wings of the soul.”

[One small addendum: My gracious correspondent Nikki Hatzilambrou reminds me that there is a connection between Les Troyens, my favorite opera, and Star Trek: First Contact, my favorite among the later “Trek” films and maybe the most heroic of them all. Captain Jean-Luc Picard is revealed in his ready room listening to “Vallon Sonore,” the opening aria of Act V of Berlioz’ masterwork.]

Wernicke dresses the Trojan

Submitted by mpresley on Sun, 2010-04-25 14:07.

Wernicke dresses the Trojan soldiery in black military uniforms deliberately reminiscent of Nazi SS regalia. He has them carry American M-16 rifles...

This sort of thing has been going on in opera longer than anyone wants to remember (for the younger generation it's longer than they can remember), and while I'm not intimately acquainted with Berlioz, I'm always saddened (but not surprised) to read about it. At least this is not too offensive, but is about what can be expected for the price of a ticket. Indeed, some would feel cheated without it. And, it's been done over and over so it's not as if the producer is covering new ground. More boring than offensive, we ought to count our blessings; unlike, say, Peter (not the dead actor--who would have done a better job) Sellars' Pelleas featuring a wheelchair bound Arkel with what has been described as a colostomy bag.

The question, of course, is why? The erstwhile NY Times music critic, John Rockwell, knew that it was because directors and conductors today understand more than the work's authors. How they understand more is not really explained very well...they just know. On the other hand, perhaps he is on to something when he once wrote that Willard White (the famous Jamaican baritone) as Goulad pushes modern realism to the limits. I think it is just beginning to scratch the surface of our modern reality, though.

One thing is certain, producers do possess a conceit that they understand the historical, psychological, and spiritual depth of the artwork better than the composer and/or librettist. I'm surprised they haven't taken to changing the score, actually. But that would require some real talent.

On First Reading Bertonneau's Berlioz

Submitted by Capodistrias on Thu, 2010-04-22 16:04.

Silent, upon a peak on Kappert Isle

With a wild surmise I await our fool to arrive.

The fog rolls in, is that Gaddafi in disguise?

No, it's Kappert building minarets in the sky.

@Prof B.

Sorry. Thank you for another fine article.