The Rotten Heart Of The Union

From the desk of Henrik Raeder Clausen on Thu, 2010-01-21 12:58

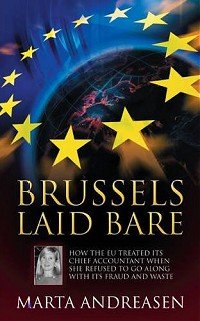

There's a lot invested in the European Union. Not only money (to the tune of €100 billion a year), also massive amounts of confidence from Europeans towards the Union, assuming that it will protect citizens / consumers from the evils of dangerous products, exploitative business and the dangers of the independent nation-state, all while protecting democracy and citizens' rights. Former Chief Accountant Marta Andreasen has a discouraging tale to tell.

First, a bit of history. Marta Andreasen was hired in January 2002 as Chief Accountant responsible for the EU budget at large, with the specific additional task of initiating reform of an obviously deficient system of accounting that each year permitted billions of euros to vanish, pure and simple.

A case of corruption had in 1999 brought down the European Commission led by Jacques Santer, and the clear message from the European Union was that now it was time for zero tolerance of irregularities and waste. After all, it is taxpayer money we entrust the European Union, not money earned by the Union directly. We should expect that money to be spent responsibly, or not spent at all.

Marta Andreasen was hired to put the required reforms into effect. However, she was dismissed after less than five months in office, a dismissal that led to a lengthy legal process, but no reform. This book is her account of what happened.

For the benefit of those who do not want to read the complete essay, my opinion is:

Well worth reading, 4 of 6 stars.

The main upside of the book is that it provides a candid view of a world not frequently exposed to scrutiny or criticism, a view with a long sequence of disturbing events of neglect and miuse of power. This is not a healthy situation for the organisation that, more or less visibly, runs things throughout Europe. The downside is that the book is lacking in structure, has few references, and has the narrative laced with countless judgements, making it much more subjective than need be, and thus subtracting from its quotability and impact.

Then, for the book essay proper:

Accountants bring accountability

What Marta Andreasen was hired to do was a task of immense responsibility. Reforming the accounting system of an organisation with a € 100 billion budget is huge. The problem, of course, was that accountability was lacking throughout the union, which led to not only missing billions, but also to the embarrassing case of Édith Cresson that eventually brought down the Santer Commission.

Such cases are usually symptomatic of deeper problems, which were amply demonstrated by the fact that the EU accounts had not been properly approved since 1996. Paul van Buitenen had filed a report about the problems, stating in his conclusion:

I found strong indications that . . . auditors have been hindered in their investigations and that officials received instructions to obstruct the audit examinations . . . The commission is a closed culture and they want to keep it that way, and my objective is to open it up, to create more transparency and to put power where it belongs - and that's in the democratically-elected European Parliament.

Predictably, he was suspended from his position, for the offense of disclosing facts to the public.

After the fall of the Santer Commission, Romano Prodi made a public pledge that henceforth there would be zero tolerance of fraud. The European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF) was created, to make it visible that the European Union was taking effective measures against fraud, and to send a strong signal to the public of problems being addressed, that the Union would self-correct.

The problems run deeper than that.

Now, one of the problems in dealing with this material is that it contains severe allegations against public figures and the way the European Union is conducting its affairs. Many of the allegations made by Marta Andreasen cannot be independently verified, as employees of the European Union have a pledge of loyalty towards the organisation and will not publicly confirm or deny the problems indicated by Mrs. Andreasen.

However, the fact that a decade has not brought convincing progress towards fulfilling the promise of zero tolerance given by Romano Prodi, is a clear indication that the problems reported by Marta Andreasen are substantially correct. Not only that, it also proves that sufficient measures have still not been taken to eliminate fraud and waste in the Union.

There are those who say that the European Union should adhere to the same level of accountability as public companies. They are wrong, for a simple reason: Private companies are accountable for only their own money. If they waste them, they will eventually go out of business.

The European Union, on the other hand, is spending money of other people, the European citizens and taxpayers. Each EU citizen contributes an average of € 200 a year to keep the Union running. As citizens, we have every right to demand that the money is spent in a disciplined and transparent way, understandable to anyone interested.

A distinct, equally important reason to expect much more discipline and transparency than a private company is the fact that the European Union cannot go bankrupt. Wasting € 10 billion a year, 10 percent of the budget, would quickly kill off a business entity. This makes good accounting and accountability a must for a commercial business. The European Union is not subject to this market-induced responsibility, and must therefore provide that at its own initiative.

Honesty and flawless accounting, mercilessly transparent to the press and the public, should be expected from the Union.

Enter Marta Andreasen

It was a somewhat unclear hiring process that led Marta Andreasen to assume the office of Chief Accountant in January 2002. Her predecessor had resigned for somewhat unclear reasons, and Marta was expected to pick up the work in a speedy fashion. First and foremost she was to sign off the accounts from 2001, and launch a plan for throughout reform of the system. Seemingly a perfect match for a high-level accountant like her.

Now, a key feature of a professional accountant is accountability, that she will not sign off accounts or authorize payments without certainty that they are sound and well documented. The official numbers showed an impressive 'margin of error' of € 5 billion, yet her own investigations led her to conclude that the true figure was a staggering €15 billion unaccounted for. The Director General and the Commission expected her to take responsibility for this, which she refused, pointing out that not only could she not put her reputation on line for such massive deficits, but also that it was really the responsibility of her predecessor to sign off the accounts for the previous year.

About the relations between Director Generals and Commissioners a lot can be said, and Marta Andreasen does so. Power struggles play out between the DG's, who are in permanent positions, and the Commissioners, who are in theirs on 5-year terms. That gives the DG's unofficial power in the bureaucracy, which in a large, complex organisation is difficult to expose and rectify. While problematic, it's by no means a situation we should expect to improve.

A distinct problem quickly identified by Marta Andreasen sounds too simple to be true: The accounting software used was inadequate. While spreadsheets are great for calculations and analysis, they are not usable as accounting systems, for the simple reason that no user logging takes place. If desired, anyone can change figures in a spreadsheet without setting electronic trails. Thus, fraud can happen undetected to various degrees, as auditors will have little chance of figuring out who would have fudged the numbers. She received many reports of this taking place.

Simple problems sometimes do have simple solutions, and this one looked straightforward: If the accounting software is not providing the required accountability, change it to something that does. Better yet in this case: Appropriate software had already been purchased, licenses in sufficient numbers, and had been adopted to the purpose. Little was left to do than putting the program to use for its intended purpose. That would be at the heart of the accounting reform efforts.

Competence, meet Bureaucracy

A key problem of hiring a person of competence is that she may point out incompetence. While that is ideally the reason of hiring competence in the first place, if the incompetence is too widespread and honesty too scarce, competence and honesty does not automatically win. Powerful civil servants can obstruct progress in highly diverse and creative ways, and the dungeons of bureaucratic procedure are most certainly daunting for a newcomer with few, if any, friends inside.

When Marta Andreasen insisted that her predecessor either sign off the 2001 accounts or provide a formal transfer of the accounting to her, that didn't go down well. The Director General and the Commission would much rather that she simply signed off the accounts herself, lending her credibility to the System as it was, rather than undertake the Herculean efforts of bringing the accounts up to a reasonable level.

An alternative proposal was that she would sign off her responsibility to the Director General. But that would eliminate the whole idea of having a distinct, supposedly independent, position as Chief Accountant. It is a testament to the integrity of Marta Andreasen that she refused. But it sure didn't win her any friends in a system where everyone apparently were complicit in substandard conduct. Her basic choice was this:

Sign off the unsound accounts, which would constitute complicity to fraud, or face a charge of 'disloyalty'.

As if refusing to sacrifice personal integrity and professional honesty would somehow be ”detrimental to the honour of the persons” pressing for her signature on the books. As she phrases it:

This pretty well confirmed not simply the hopelessness of my case, but the near-impossibility of anyone effecting real change within an undemocratic and essentially lawless institution: The European Union.

The Chief Accountant should, in principle, be independent of the organisation she oversees, that she is free to field relevant criticism without fear of being suspended or fired. That is, in principle. In practice there is a kafkasque twist to this, in that everyone seems bendable and subject to various forms of pressure, in order that they do not forfeit their loyalty to the System and cause devastating public scandals.

Suspension is always an option, for one reason or another, and Marta Andreasen was suspended in May 2002 on grounds that she had not forwarded her reform proposals in a timely manner. That she had only been in office for slightly over four months, and had made her proposals for reforms clear to everyone involved, made no difference. There is always a rule to break – actually one of the main purposes of having too many rules is that some will inevitably be broken – and in spite of her being formally independent and employed for 2 years, she had her duties relieved on May 23rd 2002.

The Rotten Heart of the Union

What follows, the Byzantine proceedings of legal battles, is less interesting to most. It shows again how a great bureaucracy can deal with problematic persons with impunity, but is really less important than the core issue:

The system is not only corrupt, but corrupting.

That is a harsh statement. The evidence is simple, actually: That the books are still not in order, that the accounts are still not signed off without major reservations. The yearly loss of billions of euros to unknown purposes is sufficient proof. That does not lay the responsibility squarely on any specific person(s), it merely goes to show that the system is still not working properly.

What makes this not merely corrupt, but also corrupting, is the fact that this siphoning off of money is rewarding and encouraging fraud. The exact kind of fraud has great variety, be it Greek farmers overreporting their livestock or Luxembourg farmers reporting more land than physically exists. Significant and very rewarding opportunities exist in this system.

Money is the lifeblood of any large organisation, and the European Union is no exception. Responsible and transparent accounting is crucial to uphold public confidence in the system, yet something is still severely amiss. Dishonesty cannot be tolerated at such a deep place of the European Union.

Accounting in the Union is still billions of euros from perfect, but since the trials and tribulations of Marta Andreasen, no significant whistle-blower has stepped up to provoke the impetus to actually deliver on the promise of Romano Prodi: No tolerance for fraud.

One of the problems is that in a private company, incompetent staff would report lacklustre results or even deficits, leading to demotion to give way for persons of greater competence. No such mechanism exists in a publicly funded bureaucracy. The larger the system, the more individuals become complicit to malpractice and eventually sacrifice their integrity to the System, rendering it unreformable.

The back cover of the book has several endorsements, including this by Lord Pearson of Rannoch:

If you want to go on hoping that the EU can be ”reformed from within”, don't read this book.

Personally, I don't hope it is this bad. I would love to see a European Union back on the democratic track, respecting the sovereignty of the nation-states and – as a matter of cause – provide complete and transparent accounting of the money and the confidence we have in this grand institution. It is vital, for it rules our lives and our countries more than most people are aware.

The only way you'll get the

Submitted by olog-hai on Sun, 2010-01-24 03:24.

The only way you'll get the EU onto the "democratic track" (saying "back" is erroneous, since it never was on the track in question) is by force now. Better hurry up before they decide to implement their common defense policy. Do yourself a favor and do an internet search for the "Red House Report".