The Flemish Influence on the American Pilgrims - Part 4

From the desk of David Baeckelandt on Thu, 2009-08-20 10:38

Recap of Earlier “The Flemish Influence on the Pilgrims” Blog Postings

In my earlier postings, Part 1, Part 2, & Part 3, we saw that from the time Flemings stormed across the English Channel as the largest component of William the Conqueror’s Invasion Force in 1066 up to the birth of the first Pilgrims in the late 16th century Flemings in the British Isles came, saw, influenced, and assimilated. The steady influx of Flemings to the British Isles in every subsequent century earned for the Flemish William Caxton’s classification by the 16th century as one of the ‘seven races of England’.

Thus, by 1600, many who spoke the King’s English and went by ‘English’ names were in fact of direct Flemish descent.The Flemish ‘swarming’ over the course of those 500 years prepared the crucible of the English body politic for the smooth reception of Flemish ideas of work and worship. Thus the late 15th century Catholic best-seller of Flemish mysticism from Thomas a Kempis called the Imitation of Christ manifested itself in the willingness of Englishmen to eagerly absorb Protestant tracts. We saw that Martin Luther’s first and most vocal Protestant advocates in the Low Countries were Augustinians from the monasteries at Ghent and Antwerp and that these Flemish friars brought the Good Word back to Flanders. Not only tracts but the English Bible itself was first financed and then prepared on Flemish printing presses at Antwerp and brought over by Flemish printers who trafficked for the benefit of both God and Mammon.

The dominance of Flanders in printing, literacy, and trade combined with this early enthusiasm for reading and disseminating the printed Word of God set the stage for the English Reformation by producing the very first Protestant martyrs – who were also from Antwerp. Flemish Protestants, often acting in league with the Flemish diaspora in England, financed and sheltered the Fathers of the English Reformation, made their work of translating the Bible into English possible and distributed the fruits of their work. In some cases they not only married themselves to the cause of the English Reformation but, as in the case of John Rogers’ wife/Jacob Van Meteren’s niece[i], even married off their daughters to make certain the cause of English reformation prospered.

At the same time, as we have seen (with more to follow), Flemish artisans brought needed skills to economically depressed regions of England[ii]. We have seen a glimpse of that in the earlier transfer of weaving skills in Bristol, Manchester, East Anglia, and select quarters of London proper. Oftentimes these artisans were migrants and moved freely and frequently between Flanders and England. Their skill sets, connections, and willingness to work harder and for lower wages sparked both envy and admiration. The Flemish immigrants’ mix of fervor and frugality meant that some Englishman saw examples to be emulated while others saw “strangers” whose radicalism was worse than treason.

In the last blog, Part 3, we chronicled the instances of Flemish and English Anabaptists being caught and martyred together for their faith from the 1530s to the 1550s. We also saw the issuance and re-issuance of proclamations prohibiting secret prayer meetings and bible-study – often conducted in nocturnal rural settings or private homes – but also the ‘separateness’ of these conventicles from regular attendance at Church of England services.

The belief of these charismatically-led, Anglo-Flemish Anabaptists in the need to separate themselves from ‘corrupt’ nationally- sanctioned parish churches and establish covenants of believers around tenets which included adult baptism while removing ritual acts were templates that English Separatists copied. The fact that English, Scottish and Flemish Protestants were caught and martyred together proves a connection more complete than mere documents can. Ignoring harsh edicts and the threat of confiscation, banishment and burnings, Englishmen were inspired by the sufferings of the Flemish “Strangers” in their midst and later linked the turning point of their conversions (to evangelical Protestantism) to those sad events. Interestingly, fruitful unions between Englishmen and Flemish women from John Rogers (English Bible translator) to John Hooper (conformist Anglican bishop) multiplied partisans on both sides of the debate.

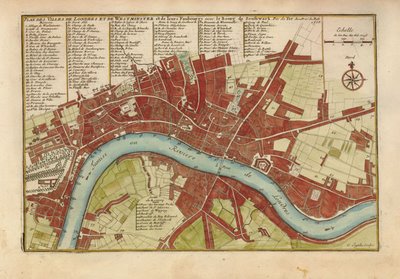

English authorities’ failure to stamp out what they considered treasonous heresy from economically critical Flemish artisans pushed them to radical action: sanctioning the existence of ‘separate’ churches for the “Strangers” in their midst. These separate churches were intended as a solution but in fact they became (as we shall see) both a template of what was possible and a further catalyst for English religious dissenters. That these first “Dutch” churches – in London, Norwich, Sandwich, Colchester, Ipswich, and elsewhere – were predominantly Flemish congregations is proved by recent scholarship. Unfortunately, as we shall see, dissension between Anabaptist and Calvinist Flemings often played out to a broader English and European audience, to the discredit of the Flemings, and to the dismay of their congregations.

We also saw – in print and in text – that the inspiration for so many English Protestants was in fact not only the written Word of God in the Bible but also the ‘best-seller’ of late 16th century England: John Foxe’s Acts and Monumentes. This book leapt across religious schisms in 16th and 17th century England as a source of inspiration. And although the term ‘Anabaptist’ was not an acceptable one in Elizabethan England, the fact is that the majority of the ‘martyrs’ were Anabaptists and a majority of the Anabaptists were Flemings.

The role of Flemish Anabaptism in furthering the English Reformation through the seminal year of 1558 and beyond is undisputed. This Flemish connection with English Separatism has been largely ignored by mainstream historians. Few have had a reason to accent the connection between Anabaptism and Separatism. Fewer still the real tie between the Flemish, the Pilgrims and the Puritans.

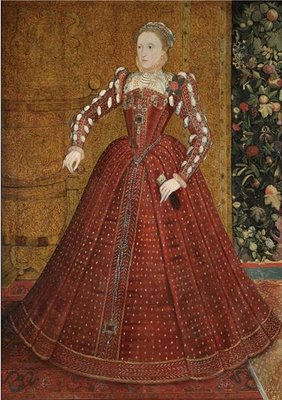

Our previous posts, then, brought us up to the end of Queen Mary’s reign. This posting will carry us halfway along the near half-century of Queen Elizabeth’s rule (1558-1603) and to the dawn of the Pilgrim Fathers’ journey to the Netherlands and the New World.

Elizabeth I’s Restoration of the English Reformation

The year 1558 was a watershed in British history. England lost its last toehold in France (Calais) – a psychological shock since French territory had been ruled from London since the Norman invasion of 1066. England also lost her Catholic Archbishop, her Catholic Queen (Mary), and of course ultimately her tie to the Church of Rome. In exchange the English gained a monarch of exceptional talent, skill, brilliance – and of Flemish ancestry: Queen Elizabeth I[i].

Regardless of her pedigree and intelligence the 25 year old Queen Elizabeth, had critical concerns to address. Uppermost for Elizabeth was the need of the Realm for temporal stability amidst spiritual turmoil. These concerns were of course no different than the preoccupations of her father Henry VIII (1509-1547) her brother Edward (1547-1553), or her sister Mary (1553-1558) for the half-century before. Ever mindful of how the religious debates of the Reformation on the Continent had quickly degenerated into warfare and brigandage, Elizabeth believed that what England needed was a middle road leading to national conformity. Although Elizabeth herself might not have so quipped, she wanted neither Papist nor Puritan to prevail.

.jpg)

Under her father Henry VIII (whom Elizabeth deeply admired[ii]) Anabaptist ‘pests’ and ‘radical’ Protestants had been hurried to their Maker. Elizabeth’s sister Mary surpassed their father’s vigor in this. Perhaps as many as 500 Protestants and Anabaptists suffered – and contemporaries underscored that under Mary a “notably high proportion of artisans” were martyred.[iii] In fact, the first Protestants burned under Mary (in 1555) and the last ones burned under Elizabeth (in 1575) were Flemish cloth workers[iv].

While Elizabeth retained many of the trappings of Catholicism in her personal devotion[v], she herself had intentionally chosen close political advisors with unquestionable Protestant credentials[vi]. Unsurprisingly, Elizabeth strove for a middle path between the rituals she inherited from Rome and the firebrand evangelism propagated from Geneva. To reach this accommodation Elizabeth marked a legal path between the two.

First, in The Act of Uniformity, (1559) Elizabeth required every inhabitant of the kingdom to regularly attend Mass (or be subject to fines and worse). All clerics were required to use the Common Book of Prayer as their sole guide to conducting the liturgy. Elizabeth followed the Act of Uniformity with the requirement (The Act of Supremacy -1559) that every candidate for higher clerical office swear a personal oath of allegiance to her. Collectively these acts were known as the Elizabethan Religious Settlement. These acts signaled Elizabeth’s desire to subordinate dictates of conscience to the diktat of realpolitik.

On one hand, these Parliamentary Acts earned England, after the Catholic interregnum under Queen Mary’s reign (1553-1558), a spot in the vanguard of the Protestant Reformation. On the other hand, these acts seemed suspect to Calvinists in England and on the Continent. Although they stabilized the English political landscape, radical Protestants – such as Separatists and Puritans – were neither pleased nor praising of Elizabeth’s chosen path.

Religious Dissent in Flanders 1558-1570s

In Flanders and the Netherlands as a whole, several developments – religious, political, military, and economic – influenced Elizabethan England’s course. The most visible development was the growth of militant Protestant activism – now known as Calvinism – in Flanders. Calvin’s doctrines took root among many middle-class and aristrocratic Flemings. For the first half of the 16th century religious radicals were primarily Lutherans and Anabaptists. Put another way, “Until the 1550s the Anabaptists had virtually no rivals among the religious dissidents in Flanders.”[vii]

Pieter Titelman, the Chief of the Inquisition in the Netherlands wrote to the Regent, Margaret of Parma, on November 14, 1561 that:

“Flanders was completely infected by Menno’s teachings. During his trips he had discovered that at Ypres, Poperinge, Meenen, Armentieres, Hondschoote, and Antwerp extensive congregations were enjoying an unheard-of prosperity.”[viii] Pieter Titelman, writing further to the Regent, about the presence of Anabaptists in the Westkwartier, exclaimed: “As for Hondschoote, there is no number [of the Anabaptists] to be given; it is a bottomless abyss.”[ix]

Margaret of Parma [who rejected suggestions to more actively persecute Anabaptists], writing to William the Silent, Prince of Orange [who strongly urged her to exterminate them] in a letter dated July 25, 1566: “I have been warned that in a certain house in the new town, opposite the house of the Oisterlins in Antwerp, there are frequently meetings of the Anabaptists, early in the morning, sometimes three or four hundred persons, who meet in several shifts, not all appearing at the same time, thus not showing how many they are, since they know very well they are disliked by all other sects.”[x]

This was one aspect of the new dynamic: the arrival of a new, militant Protestantism meant that Anabaptists found themselves pursued not only by Roman Catholic authorities but also ‘outed’ and hated by Calvin’s disciples. By the mid 1560s Calvinists dominated the elites of most Flemish cities and towns. Anabaptists (now known more regularly as Mennonites) continued to be found primarily among the artisans and tradesmen.

Among those baptized ‘Calvinist’ the crystallization of theology was inconsistently precise, however. Even such seemingly stalwart upholders of the Dutch Reformed Church (read: Calvinist) as the minister of the ‘Dutch’ Church at Austin Friars in London, Adriaen Cornelis Van Haemstaede[xi] were in sympathy with Anabaptists[xii] The one commonality among all those who broke with Rome was a strong antipathy for the form and rituals of Catholicism.

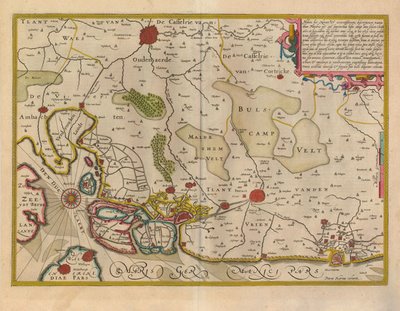

So it is perhaps unsurprising that the shift to a more aggressive, reformed Protestantism reached its apogee in the late 1560s with the outbreak in Flanders of a frenzy of iconoclasm, which in Dutch is referred to as the Beeldenstorm. The Beeldenstorm manifested itself in the smashing of religious statuary, the destruction of Catholic relics, and the sacking of monasteries. It began in the Flemish town of Steenvoorde and quickly spread throughout the Netherlands. The real smashing of statuary shattered the artificial calm between the Catholic authorities of Flanders and the radicalized populace. The shock felt by spiritual and temporal authorities prompted a vigorous military response by the Spanish.

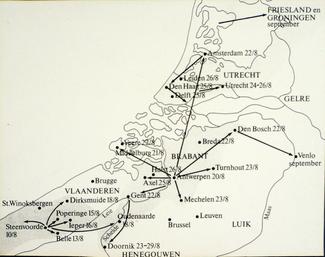

That military response to the image-breaking begun in Flanders opened the first stages of what is called (in English) the “Dutch Revolt”. The military struggle that ensued lasted for eighty years; hence, the name in Dutch, of De Tachtig Jarige Oorlog – The Eighty Years’ War (1568-1648). The outbreak of war sent tens of thousands of refugees away from the contested zone, primarily to what we today call the Netherlands, Germany, and of course England.

From the 1560s through the 1580s, the war against King Philip II of Spain went poorly for the Dutch-speakers in the Low Countries. Since a majority of the dissent, a majority of the dissenters, and a large percentage of the conflict occurred in Flanders and Brabant, this is where the bulk of the refugees came from. The strongest waves of Flemish emigration then precisely followed the Duke of Alva’s repression (1567) to the Fall of Antwerp (1585).

Other ‘push factors’ – such as poverty, poor economic conditions, famine and persecution – forced Flemish refugees, primarily Protestants but also including some Catholics, to flee their homeland. They fled from those areas overrun by the Spanish and Walloon forces to North Sea coastal areas considered part of the ‘liberated provinces’ under the control of ‘rebel’ forces. These areas were primarily coastal, and extended from Ostende to Amsterdam, what we call modern West Flanders, Zeeland and Holland. From there most caught the first skiff or sail heading toward refugee communities in southeastern England.

Civil unrest is hardly conducive to trade. When trade suffers government coffers suffer too. As Flanders was torn asunder England’s commerce with Flanders suffered too. The disruption of value-added markets for unfinished English wool exports was critical to the stability of the kingdom. Queen Elizabeth, conscious of these factors, offered enticements for skilled laborers to resettle in pockets of economically depressed East Anglia. The ‘pull factors’ of stability, economic incentives, and (after the first waves) the active encouragement of established Flemish immigrants, contributed to a further wave of ‘swarming’ during the twenty-year period 1566 to 1586.

Stranger Churches As The Example of Separatism

At a political abstract, welcoming immigrant skilled craftsmen who are also co-religionists is effortless. But of course the reality of accepting large numbers of radicalized foreigners creates its own unforeseen challenges. These include assimilation and separation. Neither is error free and both risk social disruption.

The English learned this first hand. As a leading London merchant wrote in 1575:

“After our hartye commendacons, whereas sondrye straungers borne in the Lowe countries, of late examined befor us the Quenis Majesties commissioners in their behalfe appointed, do maynteyne the most horrible & dampnable error of the anabaptistes, and in the same detestable erroure, manye of them do willfullye & obstinatelye continue.”[xiii]

Recall that Edward VI’s solution had been to permit the establishment of the Stranger Churches beginning in 1550. His hope was that segregating as much as possible the English from the influence of foreign theology and worship practices would nip the spread of heresy (defined here as anything other than the officially sanctioned orthodoxy). Ironically, the establishment of these very visible churches had just the opposite effect. As another church historian concludes, “In 1550…England’s capital was supplied with a working model of a reformed congregation as a pointer.”[xiv]

These “Stranger” churches were established along linguistic lines: Dutch, French, and Italian. The largest of these by far was the “Dutch” Church (which was also viewed as the ‘senior’ church in issues of doctrine). The ‘Dutch’ Church at Austin Friars was set up as an unum corpus corporatum et politicum. They were granted a waiver from conforming (to Church of England rules for worship) specifically with the 1549 Act of Uniformity. This meant that they were truly independent in terms of both hierarchy and ecclesiastic matters of liturgy.[xv]

The overwhelming majority of the members of the Dutch Church were, as we have seen, Dutch speakers from the Southern Netherlands – what we today call Flanders.[xvi] And, in fact, Flemings were found not only in the congregations of the so-called Walloon and French churches but, as one historian has documented, the Flemish even occupied senior positions as Elders and Ministers in the French and Italian churches[xvii].

Neither Edward nor his councilors counted on the law of unintended consequences to kick in. “Historians both of Puritanism and of the English Reformation rightly point to the importance of the example of the foreign refugee churches in London during the reign of Edward VI as providing a valuable precedent, both for the London congregation under Mary and for later Separatist developments.” [xviii] This example chartered clandestine congregations not unlike the first conventicles of Pilgrims. As we shall see there was plenty of channels for cross-fertilization.

Flemish Refugees Bring Foreign Crafts and Foreign Ideas

The English monarchs and their counselors when they established the ‘Dutch’ Church in 1550 could not have anticipated great numbers of Flemish refugees in England. But events overtook them.

Englishmen living near the Flemish colonies of Norwich, Colchester, Sandwich, and Yarmouth, “’were the first that made separation from the reformed Church of England.’”[xix] Chief among the reasons was the simple fact that the native and immigrant lived in close proximity and lived, worked and worshipped in the same venues. In Norwich, England’s second largest city and where the Flemings comprised anywhere between 30% and 50% of the total population between 1570 and 1620, the same church, St. Andrews, served both the Dutch-speakers and Separatist preachers like Robert Browne (spiritual father of Separatism) and the Pilgrim Fathers’ own pastor, John Robinson[xx]. It is hardly a coincidence then that the radicalized thought of these Flemish immigrants should flower in the faith of the Pilgrim Fathers.

Flemings and Englishmen intermarried (as can be seen from the records of the Pilgrims themselves) and native English ministers learned Dutch to assume positions in the Dutch Church.[xxi] So it should be little surprise that among seven Separatists discovered and arrested as a group in 1550, were 6 Englishmen and at least one with a Flemish-sounding surname. The Anglo-Flemish chronicler John Strype, historians’ main source for this information, believed these first Separatists (of 1550) were Anabaptists.[xxii]

In 1560 the Spanish ambassador estimated that there were 10,000 refugees from Flanders. By 1562 he estimated that there were more than 30,000 refugees from Flanders. After 1567 the numbers increased even more. Some historians believe that the total number of refugees from Flanders exceeded 100,000 in the second half of the 16th century. While these numbers even today would cause dislocations. In a near-medieval country of only 3 million souls, 100,000 immigrants quickly overwhelmed most charitable organizations.

“Those [Flemish Protestants] in the Netherlands [were] persecuted intolerably by the Duke D’Alva, that breathed out nothing but blood and slaughter. Great numbers therefore of them from all parts daily fled over hither into the queen’s dominions, for the safety of their lives, and liberty of their consciences; and had hospitable entertainment and harbour for God’s sake and the gospel’s; being allowed to dwell peaceably, and follow their callings without molestation, in Norwich, Colchester, Sandwich, Canterbury, Maidstone, Southampton, London, and Southwark, and elsewhere.”[xxiii]

In exchange for refuge, the English expected a technology transfer. Recall that before the widespread adoption of cotton as a raw material, the hottest selling cloths throughout late 16th century Europe were Flemish ‘says and bays’. These textiles blended silks and wools into a light, durable and comfortable cloth. Once settled in Norwich, Colchester, Ipswich, Sandwich, Yarmouth and other East Anglian towns, the Flemish weavers were required to take on English apprentices. “The direct influence of these refugees on the English people was seen in this that each foreign workman, was compelled by law to take and train one English apprentice. This law sent probably fifty thousand English boys and young men to school, not only in industry, but in republican ideas and liberal notions.”

The Flemish refugees then, greatly influenced their English hosts. Despite official and social barriers, they worked alongside, got married to, and worshipped at the same places as their English neighbors. It would be difficult for a 21st century government to inhibit the spread of ideas (one need only think of China and the internet). How much more difficult then in an early modern society? Elizabethan England, much less able than modern societies to confront the vast dislocation arising from a heavy influx of foreign refugees, was completely unable to prevent an impact from these Flemish Protestants on its own people.

As one well-respected historian summarized:

"When Alva began his rule in the Netherlands, in 1567, [the Flemish] exodus to England opened again (some had taken refuge in England during the persecutions under Charles V), and on a large scale. They were industrious and moral, and as good mechanics [=artisans] would have been welcomed by the government. But, although received and given shelter, they excited the indignation of the English prelates by their heretical doctrines, insisting on the necessity of adult baptism, and declaring that the Saviour died for the redemption of all mankind, and not for that of a select few. Two [of 21] of them, as we have already seen, were for these heresies burned at the stake so late as 1575, by order of the queen [Queen Elizabeth I]. But apart from these heresies, they proclaimed another doctrine still more monstrous in the eyes of a monarch like Elizabeth. Turning for their religion to the Sermon on the Mount, they taught that all oaths, courts of justice, and officers of magistracy were unchristian, and, above all, that the civil government had no concern with religious matters. Here, for the first time, the doctrine of a separation between Church and State was proclaimed on British soil."[xxiv]

Future postings will make the direct connection between the Flemish immigrants and the English Puritans to America, and the seed they planted for the establishment of the United States of America.

Endnotes

[i] For Elizabeth’s fluency in Flemish please see http://www.sparknotes.com/biography/elizabeth/section1.html . On Van Meteren, a Father of Flemish America, please see a future posting to this series.

[ii] There is an entire literature around the Flemings in England and their influence on English religious practices, economic development and political ship of state. Later postings will underscore the direct connections. A starting bibliography would include: Marcel Backhouse,The Flemish and Walloon Communities at Sandwich During the Reign of ElizabethI (1561-1603), (Brussel: Koninklijke Academie voor Wetenschappen, Leteren an Schone Kunsten, 1985); Nigel Goose and Lien Luu, eds., Immigrants in Tudor and Early Stuart England, (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2005); Ole Peter Grell, Calvinist Exiles in Tudor and Stuart England, (Brookfield: Scolar Press, 1996); Andrew Pettegree, Foreign Protestant Communities in Sixteenth-Century London, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1986); and Randolph Vigne and Charles Littleton, eds., From Strangers to Citizens: The Integration of Immigrant Communities in Britain, Ireland and Colonial America, 1550-1750, (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2001), esp. pp: 1-230; 353-412.

[iii] B.R. White, The English Separatist Tradition: From The Marian Martyrs to the Pilgrim Fathers, (Oxford: University Press, 1971), p.3

[iv] Twenty-one Flemish Anabaptists were betrayed on Easter Sunday, subject to torture and burned for their beliefs at Smithfield in 1575. See http://www.gameo.org/encyclopedia/contents/jan_pietersz_wagenmaker_d._1575 for details in English. Note that many of these early martyrs came from Gent.

[v] See Alice Hunt, The Drama of Coronation: Medieval Ceremony in Early Modern England, (Cambridge University Press, 2008), pp.152-155. See also, David Starkey, Elizabeth: The Struggle for the Throne, (New York: Harper Collins, 2001), pp. 295-299 for Elizabeth’s retention of not only Roman Catholic vestments and practices but also other Roman Catholic paraphernalia in her household as late as 1600. See also Leo Frank Solt, Church and State in Early Modern England, 1509-1640, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990), for background.

[vi] These key advisors included William Cecil, Lord Burghley and Matthew Parker, who became the new Archbishop of Canterbury. But she also retained several advisors from her Catholic sister Mary’s reign as well.

[vii] Marcel Backhouse, The Flemish and Walloon Communities, op.cit., p. 63

[viii] A.L.E. Verheyden, Anabaptism in Flanders, 1530-1650: A Century of Struggle, (Scottdale: Mennonite Publishing, 1961), p.55

[ix] ibid, p.56

[x] ibid, p.62, n.96

[xi] "Haemstede, Adriaen Cornelis van (1525-1562). Adriaen Cornelis van Haemstede, of noble lineage, attended the University of Louvain, where he published in 1552 Tabulae totius juris canonici, . . . Livino Bloxenio á Burgh dicatae (copy in the State Library at Munich). He apparently joined the Reformed Church soon after. From Emden he was sent to Antwerp at the urgent request of the Reformed Church (dated 17 December 1555), and preached there in homes and out-of-doors. From autumn 1557 to February 1559 he spent a second period in Antwerp, full of danger and difficulty. In this period he wrote his chief work, the martyrbook, De Gheschiedenisse ende den doodt der vromen Martelaren, the om het ghetuyghenisse des Evangeliums haer bloedt ghestort hebben, van de tyden Christi af, tot ten fare M.D.LIX toe, byeen vergadert op het kortste, Door Adrianum Corn. Haemstedium. An. 1559 den 18. Martii. The book is of great value, with its carefully collected and highly reliable reports, and was reprinted at Dordrecht 1657, Brielle1658, Dordrecht 1659, Amsterdam 1671, Doesburg 1870-1871, Doesburg 1883. His influence on Tieleman van Braght's Martyrs' Mirror is unmistakable.

In his report on Anthonie Verdickt, who died in Brussels 12 January 1559, there was in the edition of 1559 (p. 449) a statement of Verdickt's very liberal view on early or late baptism, which has been deleted from all subsequent editions. Sharpened denominational sensitivity is also shown by the fact that because of Haemstede's mild judgment of the Anabaptists his name has been omitted from all the editions of his book since 1566 (Dresselhuis, 67; Sepp, 12). Worthy of note is also Haemstede's Confession of Faith for the Reformed in Aachen (1559) (Goeters, Theologische Arbeiten, 82 and 91). The following Anabaptist martyrs are found in Haemstede's martyrbook: Wendelmoet Claesd., Anneken vanden Hove, Sybrand Jansz,Janneken de Jonckheere, and Laurens Schoenmaker.

Fleeing from Antwerp, Haemstede led 13 merchant families to Aachen in February 1559 (not 1558; see Goeters, 55 ff.; 1907, 27), obtained permission to let them enter, preached to the citizens, had dealings with the Anabaptists, and preached in Jülich (Redlich, II, 375-381).

When Elizabeth assumed the British throne he sought refuge there for his fellow believers. In May 1559 Haemstede was in London, and was given the right to preach to his countrymen in Christ Church or St. Margaret's. In a letter to Palatine Elector Frederick III (12 September 1559) he pleaded for intervention in behalf of the Reformed in Aachen and sent a very instructive confession of faith for them (Nederland Archief, 1907, 46 ff.; Theologische Arbeiten, 1906, 85 ff.). But he soon became involved in a serious dispute on account of his mild judgment of the Anabaptists. On 3 July 1560 the church council of the greatly increased congregation charged Haemstede with offering the hand of brotherhood to several Anabaptists, though they rejected him; on the question of the incarnation he confessed his ignorance and declared that he would not for that reason reject the Anabaptists. Indeed, he had to intercede for them to the magistrate, to the bishop in London, whom the queen had appointed as supervisor of foreign groups, as well as to the Low German Reformed Church. They did not teach, as theMünsterites had, community of goods or of women; he would not judge them harshly. An anonymous petition was actually presented to the bishop of London, Edmund Grindal, to tolerate several who were unable to unite with the Reformed group. On 4 September the bishop sent it to Petrus de Loenus and Jan Utenhove for their opinion (Strype, Grindal, 62 f.). Haemstede admitted that he had promised to speak for them, not because he sanctioned their doctrine of the incarnation, but because he hoped they would see the light; at any rate, they were weaker members of Christ. They replied with the reproof that to underestimate error is to confuse the believers, strengthen the opposition, and make the church suspect in England and elsewhere. Instead of making the confession of guilt required of him, Haemstede declared that persons who acknowledge Christ as priest and intermediary, desire the Holy Spirit in order to work righteousness, are founded upon Christ, the only foundation. Hence he hoped for the best for them as for all his dear brethren. Even if they built on this foundation with wood, hay, straw, or stubble, they could partake of salvation. Their great ignorance did not exclude them from salvation. The truth should be presented to them in friendliness, but to judge and condemn them as ungodly was of the flesh and forbidden. Galatians 5; Matthew 7. This judgment refers not to all, but to the good among the Anabaptists, who err in simplicity (Kerkeraadsprotokollen, 448). The council replied that then no church discipline could be exercised toward those who joined the Anabaptists. Whoever rejected the incarnation, infant baptism, the oath, and government, refused to join the church, could not possibly be considered a brother. Haemstede agreed with a document of this nature, but added: the question of the method of incarnation was only a minor point in the article that the Son of God truly appeared in the flesh. To separate on this point would be to cast dice for the garment and to neglect the Crucified, or to quarrel about the color of the garment.

On 5 August 1560, Haemstede was suspended from the office of preaching. He replied, "Do these things, it is well, I thank you; this is what I seek. Christ ought always to suffer at the hands of the scribes and Pharisees; his ministers suffer likewise. But I must preach the Gospel; the Lord will provide the place for me" (Kerkeraadsprotokollen, 455).

In further negotiations before Bishop Grindal on September 16 Haemstede signed a correct confession of the incarnation, but refused to make a confession of guilt, and was therefore excommunicated on 19 November 1560, and expelled from the country. His adherents long maintained that he had been unjustly sentenced, and were themselves excommunicated. Among them were such distinguished men as Acontius, the historian Emanuel von Meteren, Antonius Corranus, and Cassiodorus de Reyna.

Haemstede went to Holland, where he worked in The Hague, East Friesland, and later inGroningen. There is also record of a trip to Kleve (121). In Antwerp a document in his defense was circulated (170). Also in the church council of Emden opinion was in his favor, and they wrote to the London church and to Grindal to have the case reopened. But when Haemstede appeared in London on 19 July 1562 to preach, and looked up his followers, he was arrested on 22 July. Grindal rejected as inadequate and ambiguous the confession of guilt presented by Haemstede and presented to Haemstede a formula of recantation (Strype, Grindal, 469 f.), in vain. An edict of the Privy Council to the church commissioners, 19 August 1562, ordered him to leave England within 15 days or forfeit his life. He died in Friesland in that year. The influence of Haemstede's attitude toward the Anabaptists continued not only in England. In Holland and East Friesland voices were heard in their defense. A very similar case soon after Ulis is that of the Walloon preacher, Adrian Gorinus."

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Scottdale, Pennsylvania, and Waterloo, Ontario, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 2, pp. 620-621. All rights reserved. For information on ordering the encyclopedia visit the Herald Press website. ©1996-2009 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.

Goeters, W. G. "Haemstede, Adriaen Cornelis van (1525-1562)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1956. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 27 July 2009

[xii] Adriaen Van Haemstaede in fact lost his position as the head of the Dutch Church in 1571 for opposing the burning of Flemish Anabaptists in England. As a result, the Antwerp native Emmanuel Van Meteren, the leading ‘Dutch’ representative in London and the son of the financier of the first English Bibles (Jacob Van Meteren) left the Flemish/Dutch Church and became a communicant at the Italian and French (protestant) Churches. Given his stature in the community it is likely that he carried with him other Flemings.

[xiii] Stephen S. Slaughter, “The Dutch Church in Norwich”, April 21, 1933, p.92 from an edict dated June 7, 1575 from London, quoted in Book of Orders for Strangers, folio 81d, p. 183

[xiv] B.R. White, The English Separatist Tradition, op.cit., pp.4-5

[xv] Timothy George, John Robinson and the English Separatist Tradition, (Macon: Mercer University Press, 1982), p.13.

[xvi] For example, not only was the origin of the Deacons and Elders overwhelmingly from Flanders (The Top Five origins for Deacons & Elders were Antwerp, Gent, Brugge, Roeselare, Kortrijk) but the congregation too was overwhelmingly Flemish (The Top Five places of origin for brides and grooms were Antwerp, Gent, Brussel, Brugge, and Oudenaarde). See: Raymond Fagel, “Immigrant Roots: The Geographical Origins of Newcomers from the Low Countries in Tudor England”, in Immigrants in Tudor and Early Stuart England, op.cit., p. 48, Table 2.3 “Geographical Origins of Elders and Deacons of the Dutch Church, 1567-1585” and also p. 49, Table 2.7 “Geographical Origins of Deacons and Elders, Brides and Grooms in the Dutch Church, 1571-1585 – Top Six Places”. Incidentally, The Flemish even heavily contributed to the leadership of the French and Italian Protestant churches. Antwerp, Gent, Brugge were in the Top 5 of place of origin for the Italian Church – See Ibid, p. 48, Table 2.5 “Geographical Origins of Elders and Deacons of the Italian Church, 1568-1591”. Note also that the first place of origin for ministers for the French church was Antwerp. See Ibid, p. 48, Table 2.4 “Geographical Origins of Elders and Deacons of the French Church, 1567-1585”.

[xviii] B.R. White, The English Separatist Tradition, op.cit., p.2

[xix] Timothy George, John Robinson, op.cit., p. 10; quoting John Strype, Ecclesiastical Memorials, (Oxford, 1822), vol.2, pp.70-71.

[xx] Ernest A. Kent, “Notes on the Blackfriars’ Hall or Dutch Church, Norwich”, undated book excerpt pp. 86-108. pp.98-99

[xxi] ibid.

[xxii] Timothy George, John Robinson, op.cit., p. 11; quoting John Strype, Ecclesiastical Memorials, (Oxford, 1822), vol.2, pp.70-71.

[xxiii] John Strype, Annals of the Reformation and Establishment of Religion, and Other Various Occurences in the Church of England, During Queen Elizabeth’s Happy Reign: Together with an Appendix of Original Papers of State, Records, and Letters, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1824), p. 269

[xxiv] Douglas Campbell, The Puritan in Holland, England, and America : an Introduction to American History, (New York: Harper, 1892), vol II, pp. 178-179

This article was originally published on the "Flemish American" weblog.

Thank you

Submitted by debendevan on Fri, 2009-08-21 16:16.

Thank you Traveller! I very much appreciate your kind words. But the best parts are yet to come.

My hat is off to onze Vlaming voorouders who blazed the paths described above and in future posts but died without recognition.

With warm and friendly greetings,

de bende van

@ David Baeckelandt

Submitted by traveller on Thu, 2009-08-20 18:27.

I don't know how you did it, but your work is brilliant