Zombie Governments

From the desk of Richard Rahn on Fri, 2009-07-31 17:06

If the U.S. trade deficit were to disappear, do you think that would be a good or bad thing?

For years, many in the media and the political world wailed about the U.S. trade deficit, but it is rapidly disappearing -- and the consequences are going to be disastrous.

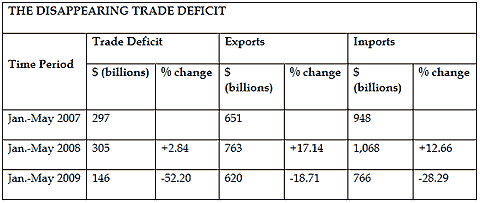

The table shows the U.S. trade deficit dropped 52 percent between January and May of this year, as compared to the January-through-May periods of the two previous years. During the same interval, exports of goods and services dropped 19 percent and imports dropped 28 percent. The U.S. trade deficit might disappear within the next year.

Over the past several decades, many foreign countries -- notably Japan and China -- exported much more to the United States than they imported, and as a result, they accumulated several trillion U.S. dollars.

Most of those dollars were, in turn, invested back in the United States. Foreign individuals, companies and governments bought U.S. government securities. They invested money in U.S. real estate, often spending funds to renovate old hotels and shopping centers. They invested money in the U.S. stock market and in new high-tech start-ups.

All this investment greatly benefited the United States by keeping interest rates lower than they otherwise would have been and providing more capital to U.S. businesses, which then were able to hire more workers and invest in productivity-enhancing machines and software. But it is all disappearing.

Exports have been falling faster in Germany and Italy than in the United States, and in Japan, they have been falling more than twice the U.S. rate. This means those countries, and most others, will earn fewer U.S. dollars.

If they have fewer dollars, they will have less money to invest in the United States, which means higher long-term U.S. interest rates and thus less productive investment in U.S. plants and equipment, which, in turn, will mean fewer new jobs will be created.

When trade expands because of fewer trade barriers and growing global demand, it is a win-win situation for both exporters and importers. The world's consumers have access to more goods and services at lower prices (which means they have a rise in their real incomes), and the world's producers have many more customers and thus are able to expand production and create jobs.

However, when trade declines sharply, as it is doing, the opposite happens. As exports decline, people lose their jobs, causing further declines in demand for both domestically produced and imported goods and services.

Governments cannot spend their way out of this problem. More spending leads to higher taxes or greater deficits. Higher taxes depress demand and the incentives to work, save and invest. Higher government deficits suck savings by individuals and businesses out of the productive sector into financing nonproductive government debt -- leaving less money for investment in new plants and equipment and job creation.

One international financial expert who has a long record of correctly seeing things that others have missed, Criton M. Zoakos, notes:

"In Europe, the U.S. and Japan, massive financial bailout programs ... have committed approximately $35 trillion of public funds to support financial asset prices at pre-crisis levels. ... All of these governments won initial public approval for these stupendous bailout commitments by claiming that they were needed to restore credit flows to 'businesses and households' and save jobs.

"However, the fact is that nine months after approval of these plans, and the commitment of $35 trillion, lending to non-financial businesses and to households has declined in the United States (by 5.5 %), Britain (by 5.6%), Eurozone (by 0.4%) and Japan (by 3.4%)."

The political leadership in the major economic powers, failing to learn the lessons of history, has been pursuing policies that can only result in failure, and the leaders seem to have little idea of what to do next.

Mr. Zoakos rightly calls the powers "zombie governments." Most of the opposition parties in leading countries (including the Republican Party in the United States) are all too muddled in their thinking about what to do next and hence are inarticulate about laying out solutions the body politic can understand readily.

The solutions are not rocket science and are well-known to thoughtful people:

- Reducing existing trade barriers (not increasing them as is being done).

- Strengthening property rights (not undermining them as was done in the Chrysler and GM bankruptcies).

- Reducing tax rates on labor and capital (not increasing them as the U.S. Congress and administration are in the process of doing).

- Applying strict and real cost-benefit analysis to new and existing regulations -- including financial and environmental (rather than regulating to satisfy the emotions of the "politically correct").

- Reducing all government spending by again applying real cost-benefit tests (rather than making grants to political cronies and falsely labeling them economic stimulus).

- Strengthening the dollar and other currencies by reducing debts and government financial guarantees that cannot be serviced.

Unfortunately, none of the above solutions will be undertaken soon in the United States and elsewhere. Billions of people will suffer needlessly, and the corrupt and ignorant political class will continue to lie, eat and drink at our expense.

This article was originally published in The Washington Times, 28 July 2009.

RE: Yes and no

Submitted by Kapitein Andre on Sat, 2009-08-01 07:28.

I agree in the main with marcfrans, whose counter-arguments pertaining to American reliance on foreign imports and investment strongly mirror those of David Goldman, and others whose voices had been consigned to the wilderness before our current troubles gave us pause. That the American economy could take solace in its reliance on foreigners is indicative not of strength at home, but of market failure overseas. Not only are competing economies endeavoring to rectify these failures in their credit and financial markets, but the American economy has not used its lead wisely, and must inexorably lose it. Societies can and do forfeit economic superiority in order to "enjoy" the fruits of their labors. And despite Japan's refusal to take immediate action after its own crisis, Japanese society still retained those collective characteristics that are essential to success.

marcfrans may interpret this agreement as some sort of expression of anti-Americanism. It isn't. I have always believed that culture determines success. Once, American culture comprised the "best" of Europe. Nor are Europeans innocent of rejecting their culture in favor of "modernity" or "post-modernity".

Yes and no

Submitted by marcfrans on Fri, 2009-07-31 22:26.

Mr Rahn's "solutions" (at the end of the article) are sensible ones, and they can easily be subscribed to by many who have escaped Obama-mania.

By contrast, his opening claim that the rapid decline in the US trade deficit is going to have "disastrous consequences" is more debatable. Disastrous for who? For the rest of the world the answer is probably yes, although "disastrous" may be overstating it a bit. "Negative" would be a better characterisation. But, for the US?

For a primitive, underdeveloped, and capital-scarce economy, the claim that sustained NET foreign capital imports are beneficial is believable. Growing foreign indebtedness then can make sense, for it can lead to higher indome (via greater 'real' investment) that will enable debt-servicing and, ultimately, repayment. But, for a developed economy, with abundant capital available, there clearly must be limits to growing foreign indebtedness beyond which such debt accumulation feeds 'immiserising growth' (although not in the Bhagwati sense).

-- There is no evidence of a capital shortage in the US, nor of a dearth of 'real' investment as opposed to financial investments.

-- It is doubtful that the level of interest rates has acted as a constraint on real investment in the US, and it is also likely that much of (the capital imports associated with) the US trade deficits has been financing excessive consumption rather than real investment.

Just like an individual can over-consume (relative to income), via excessive borrowing, whole nations can do so too. Borrowing is not always a good thing, as the current financial crisis has made abundantly clear. The crucial questions are: what is the total level of indebtedness relative to national income, and what are the extra borrowings used for? One can hardly claim that extra foreign borrowings to finance the large public deficits of Bush, and the even larger public deficits of Obama, could be a 'good' thing for the American public over time.

And, besides the economic considerations of continuing large American deficits on the external current account, there are political considerations (of genuine independence) too. Beggars can't be choosers....